As Mountain Valley Pipeline moves toward completion, a farmer’s fight remains

Jammie Hale, 51, looks out over his property in Giles County, Virginia, towards the Mountain Valley Pipeline—about 200 yards away.

Jammie Hale moved to a rural hilltop in Southwest Virginia to get back to his family’s roots. When the MVP came through a neighboring property, he found another purpose

By Leah Small

Photos by Christopher Tyree

The Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

Jammie Hale, 51, has lived in Giles County in Southwest Virginia his entire life, as did generations of his family before him since 1779. Giles County, which borders West Virginia, is known for its scenery – mountain vistas, covered bridges, tranquil deep woods.

But for six years, noise and disruption from start and stop construction on the Mountain Valley natural gas pipeline and dogged opposition of the project by environmentalists and area residents like Hale, has cut through the county’s rural quiet. The Mountain Valley Pipeline spans just over 300 miles between West Virginia and Southwest Virginia, crossing hundreds of streams and wetlands and under private property. Five years behind its original schedule – and billions over budget – the pipeline is expected to be operational by June.

Although the pipeline does not run through Hale’s property, the project has upended his life.

Hale, with his wife, Linda, purchased a secluded, hilltop property in 2008. They started a farm and raised livestock after buying the property in 2008. Hale plans to eventually deed the property to his son. Hale, who had worked mostly low wage jobs before farming, including custodial work at Virginia Tech, saved for decades to purchase the property.

Since pipeline construction got underway in Giles County a little over six years ago, Hale’s drinking water has been clouded by sediment. A natural spring that he used to water his animals stopped flowing, so he no longer keeps livestock. It’s unclear what caused Hale’s water issues. The Virginia Department of Environmental Quality has not investigated the water contamination on Hale’s property. The Roanoke Times has reported other incidents of drinking water being contaminated by erosion caused by pipeline construction.

The changes have crippled Hale’s livelihood.

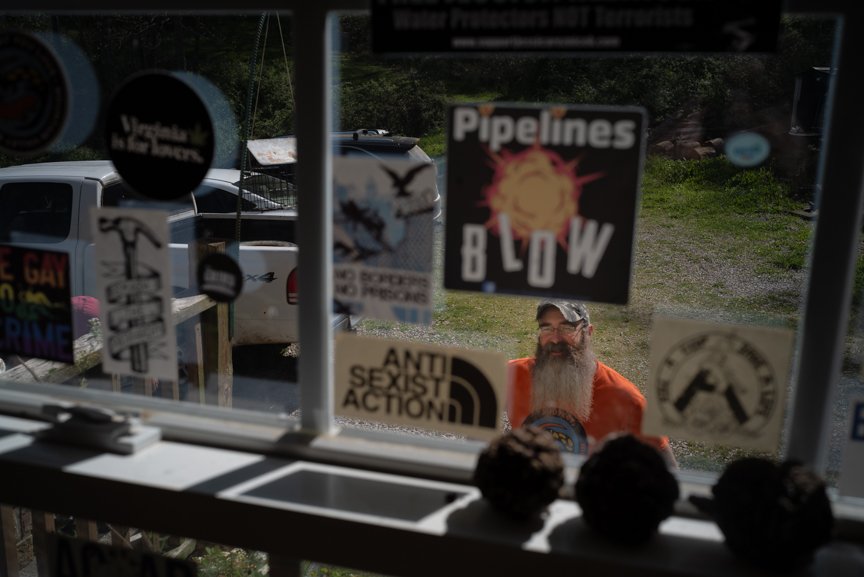

Hale has decorated his kitchen windows with stickers reflecting his sentiments towards the pipeline and his changed world view.

“It’s broken me in many forms physically, mentally and emotionally,” Hale said.

Since he can’t farm, Hale has been “on the front lines of fighting this thing every day for pretty much a little over six years,” Hale said. “That's what my life has been."

He has protested the pipeline by documenting possible environmental violations, growing food to feed tree sitters blocking access to the pipeline, painting signs and more. Hale faces a civil injunction that bars him from disrupting pipeline operations. He was arrested in Montgomery County in 2019 and pled guilty to a charge of disorderly conduct for actions related to the protests.

Hale isn’t alone in his objections. Appeals by property owners and environmentalists continue in the federal courts. Area residents also have safety concerns and fear the pipeline could rupture, releasing flammable gas that could contaminate the area. A section of the pipeline failed a pressure test in May.

But supporters say the Mountain Valley pipeline is crucial for energy security and reliability.The company says natural gas pipelines have the best safety record of any energy delivery system in the country, and the new fuel pipe will be monitored constantly by a sophisticated, high-tech system.

Significant pipeline construction delays were caused by challenges from environmental groups, including a failed Supreme Court case to prevent project construction within the Thomas Jefferson National Forest. The project has been hit with hundreds of environmental citations, including a $2.1 million civil penalty for allowing sediment to enter waterways in Giles and other counties.

Pipeline construction company EQT said it paid the $2.1 million fine and other penalties without dispute, and has worked quickly to resolve environmental violations identified by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality.

In May, DEQ issued a $31,000 fine against EQT for the company’s failure to install erosion controls, which resulted in sediment contaminating creeks in Franklin County. EQT said it has put infrastructure in place to correct the problem.

The battle to stop the pipeline from coming to Appalachia was lost, but Hale wants to continue the fight to stop the pipeline from being used.

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

landscapes in Giles County near Hale’s home.

When you're born in some of these areas and you have no way out, you have no choice but to stay here. And then it becomes a love. And you don't ever want to leave. You know, there's just no money for education. People really didn't have the money to send their kids to college. Therefore, you've got to start work at an early age.

But there's certain parts of the area that you fall in love with. First, it's the streams, the fishing and the hunting and the mountains. And over time, the whole area itself is something you want to be a part of.

I'm proud to be from Appalachia because I know how to do things. I know how to hunt and I know how to fish. I know where to find bait to go fishing with. I know how to feed myself.

I have a love for the mountains, and the trees and the flowers. I have a love for the squirrels and the rabbits that are here. And so, to be part of Appalachia, I just love that I was born here.

Me and my wife. We've been married for around 24 years. When we decided we needed to expand, we had children, and I was looking for a piece of land.

My grandfather had a farm when I was a kid. So, I always wanted to be around farm animals and in this area, everybody has cows.

I wanted to try my hand at farming. It took some time to find a piece of land, but eventually ended up finding this property. Me and my wife purchased this in 2008. I raised goats and chickens and then moved on to pigs up to the point that I was able to start buying some steers and raising a few of those.

It took me ten years, you know, to get everything kind of situated. And then the pipeline come to town. Now my pond is dried up, and I found myself with no water in my house.

I've lived here since 2008 on this property with the freedom that comes along with it. You know, my nearest neighbor is about 600 yards away. I don't hear anything out of them. You can hunt. You can set out on your own porch in your pajamas and drink coffee in the morning. It's the American dream. And that American dream is basically turned into a nightmare.

Workers on the Mountain Valley Pipeline deal with erosion that has left the pipeline partially uncovered as it nears Sinking Creek in Giles County. The site is about 3 miles from Hale’s home.

With this pipeline, we've noticed, we don't see the deer like we used to. Used to be a lot of bears around here, especially in the spring. There was a mama cub. She always brought her cubs here every spring.

It’s been about 4 or 5 years that I ain't seen her. Probably two years since they really got to start construction in this area. You’re sitting in the house, all you hear is the beeping and stuff. It just really gets under your skin.

I found out about the pipeline in probably mid to late fall of 2017, and my neighbor told me that a pipeline construction company had contacted him and was wanting to do some surveying in this area for this natural gas pipeline, which is fracked gas.

I didn't know anything about it. I started doing some googling and started trying to find out information about this pipeline. Then in early spring of 2018, surveyors came into the area and started walking over people's property …trying to survey things. And that's how I got involved. And then I really realized that this is reality, they're wanting to build a pipeline here.

My neighbor, when we were discussing this pipeline project, said, "I don't want them on my property.” He was not interested in selling. Later, I guess the money becomes so great that they had to take it. So, these people eventually sold their right of way to this construction company.

When construction first started here, they brought equipment in and started clearing the trees out of the way. In 2018, we had record numbers of rainfalls. They had so many violations from construction where they did not do sedimentation work. A lot of the mud and stuff was allowed to leave their property.

I didn't know who to contact. They never shared any information on who to talk to. I didn't know anyone local to talk to other than the county administrator. I talked to the local sheriff about it. I talked to some of the workers, security people down here at the bottom of the driveway. But nobody had an answer.

My water today, there’s still some sediment and that’s after filtration. I was 18 days with no drinking water, no running water in my house, in 2018. I had all this livestock at the time and the two spring fed ponds on my property were starting to go dry at that time.

A bench sits at what used to be the bank of a small pond, which Hale said dried up during the pipeline’s construction.

I went to this creek down here for 18 days and filled barrels of water using a rope and a bucket. And I brought it up here for my animals just because I had no other means of providing water for these animals. Some of them died.

I decided I couldn't fight the pipeline and raise animals. And with the water situation the way it was, the most important thing was to fight the pipeline.

In 2018, I didn't know anybody was fighting this pipeline. I was trying to find things and eventually I found that there were some folks who had erected a tree sit in the path of the Mountain Valley Pipeline. I would meet people and I would guide them through the mountains and those folks would take supplies to the support camp.

In 2019, I was issued an injunction through the Marshals Service. They showed up here at my house and delivered an injunction that basically said that I could not be within a thousand feet of the pipeline. They said I was blocking access to their work sites. They said I was stalking them. I've been arrested twice.

There's not gas running through it yet. So, there is still that chance (that it won’t go into operation). The plan is to allow my son to inherit this property. I always worry, if I hand this property down to my son, that him and his family could be living here and this thing explode.

In order to lay down at night, I have to do everything that I possibly can do to try to make a difference. That gives me determination. My hope for the future is that there will never be fracked gas running through Appalachia.

And I hope that with all the people that I've met fighting this pipeline project, we can all sit down and say we beat this pipeline.

Hale says he’s loved living in rural Virginia but is concerned now about his safety because the pipeline is so close to his rural property.

Reach Leah Small at leahmariesmall@gmail.com.