The case of Travion Blount illustrates how Virginia’s juvenile justice system can throw away the lives of teen offenders.

STORY BY LOUIS HANSEN

PHOTOGRAPHS BY ROGER M. RICHARDS

Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism

When I met Travion Blount, he was wearing a prison jumper and shackles.

It was 2013. I can’t remember as much as I’d like, only a large, empty room with stainless steel tables and benches. He was lanky, slouched, with his hair cut short. Two guards watched over us.

I sat across from him, holding a pencil and notebook, nervous. We were inside one of Virginia’s new maximum security prisons, a stark fortress set on a mountain ridge in coal country.

We exchanged awkward greetings. I had never been in a prison like Wallens Ridge. He had never been interviewed by a reporter.

We talked for a few hours, and he laughed often, in a youthful, nervous way. His chains rattled and echoed through the room every time he shifted in his chair.

At the end, neither of us had really figured out why his life had turned out this way.

He was 23 and had already spent nearly eight years in prison.

He hadn’t killed anyone or even fired a shot, but he carried perhaps the longest sentence ever given to an American teenager -- six life terms, plus 118 years.

He expected to die in prison. I didn’t expect my story would change that.

As Black Lives Matter protests erupt across the nation -- grievances aired, change demanded, statues toppled -- Travion Blount’s case seems relatively unremarkable. There’s no video, no murder, no police misconduct.

But his case reveals how a criminal justice system -- driven by a frightened public pushing lawmakers, year-after-year, to enact ever-harsher punishments -- can forever shackle the lives and futures of teen offenders.

Blount was 15 when he committed an armed robbery in Norfolk with two 18-year-old accomplices. He carried a gun, but never pulled the trigger and wounded no one. The others took plea deals from prosecutors for 10- and 13-year sentences. Blount refused a deal, never imagining that he’d face a harsher term.

In Virginia, a teen can commit a serious crime -- armed robbery, malicious wounding -- and still be sentenced to a life in prison.

This seems to contradict a 2012 ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court. The court concluded that sentencing juveniles to life with no possibility of parole for a crime not involving homicide amounted to cruel and unusual punishment, and was unconstitutional. Juveniles, it ruled, must be given a meaningful chance to leave prison.

But a few states came up with work-arounds to the Supreme Court ruling. Virginia courts ruled that juveniles had an honest chance to petition for release -- when they turned 60.

Under Virginia law, Blount wouldn’t get a chance at freedom for almost another four decades.

But I didn’t get into this story to learn constitutional law. I just wanted to understand how punishment could fall so heavily on one teenager.

His lawyer, John Coggeshall, described it this way: “The perfect storm of a case.”

In a way, I knew a lot about Travion Blount before we met. I’d spent hours reading thick binders of trial testimony and folders of juvenile records. I’d had his attorney go over the details of the case, his impressions of Blount and theories about what happened. I’d interviewed his parents, filled in their family history.

His parents met in traffic court and shared a brief romance. His mother, Angela Blount, worked as a housekeeper at oceanfront resorts, while his father, Patrick Mills, an erstwhile amatuer powerlifter, stocked groceries.

Angela and Patrick split up, but shared custody of their son.

Blount grew up shy, they said, running away from his grade-school classroom to avoid speaking in class. He would sometimes help his mother clean rooms in the waterfront hotels.

He hated school, and, by his early teens, he had dropped out.

In Norfolk, poor, unsupervised kids often drift into trouble. I saw them every day as a reporter covering the courts -- busted for smoking weed, dealing small amounts of drugs, waving a gun around and sometimes, killing someone.

The defendants were disproportionately Black and from families poor enough to qualify for court-appointed, and often-overworked, attorneys like Coggeshall.

When other kids were signing up for Pop Warner football and Little League, Blount joined a gang. Between 11 and 15, he was in and out of truancy hearings and juvenile courts.

On Sept. 23, 2006, Blount and two others, including his gang mentor, robbed a drug dealer in Norfolk. They showed up at the dealer’s house, surprised to see a party going on, according to court evidence. The three teens brought two guns, grabbed some marijuana, cellphones and less than $100. Police caught them within days.

Blount wouldn’t take the 18-year sentence prosecutors offered. Coggeshall said, “Take it.” Older men in the jail said, “Take it.” Coggeshall even arranged to have his parents come back to lock up -- almost unheard of in a court holding cell -- to convince him.

No one could change his mind. He went to trial.

Prosecutors loaded up the charge sheet -- 51 felonies. It took a jury just a few hours to return a stack of 49 guilty verdicts.

More than a dozen felonies carried mandatory sentences, so Coggeshall knew immediately that his client was facing more than 100 years in prison.

In a courthouse teeming with murder trials, gang-related violence and the occasional high-profile civil case, Commonweath v. Blount barely got noticed.

Several weeks later, Blount returned to the courtroom, where a circuit court judge serving his last weeks on the bench heard sentencing arguments.

Coggeshall reminded the judge that the teen’s actions drew no blood, that he and the others had stolen less cash than they’d earn working a weekend shift at McDonald’s.

Blount got six life terms. And since he had used a gun, the state mandated another 118 years.

Blount turned to his mom in the courthouse audience and asked, “What just happened?”

Later, in maximum security prison, men twice Blount’s age refused to believe the sentence until he showed them his court papers.

Maybe the judge, a former prosecutor, thought the sentence was fair. Maybe he wanted to send a message. Maybe he felt he had little choice. Or maybe he just wanted someone to look at this case again.

I really don’t know. He never returned my messages.

The sentence was heavier than the two life terms received in Virginia in 2004 by Lee Boyd Malvo, the teenager convicted of capital murder in the D.C. sniper shootings.

Few outside Blount’s family noticed or cared.

But Coggeshall -- a former nightclub singer, songwriter and self-taught lawyer known to court denizens as “Cogg” -- pressed on. He appealed to state and federal judges.

Coggeshall told me about Blount’s case soon after we met. I hadn’t covered the original trial, but I told him I wanted to write about the case for my newspaper, The Virginian-Pilot.

No, he said. Not now.

But when Coggeshall was running out of appeals, he called me. I arranged to meet Blount in prison.

Blount was shy and nervous, surrounded by much older men with long, often violent, criminal records.

He told me he didn’t feel responsible for every crime the prosecutors claimed. The offer of an 18-year sentence was longer than he had been alive.

“Who would have thought I would get six life sentences?” he asked me.

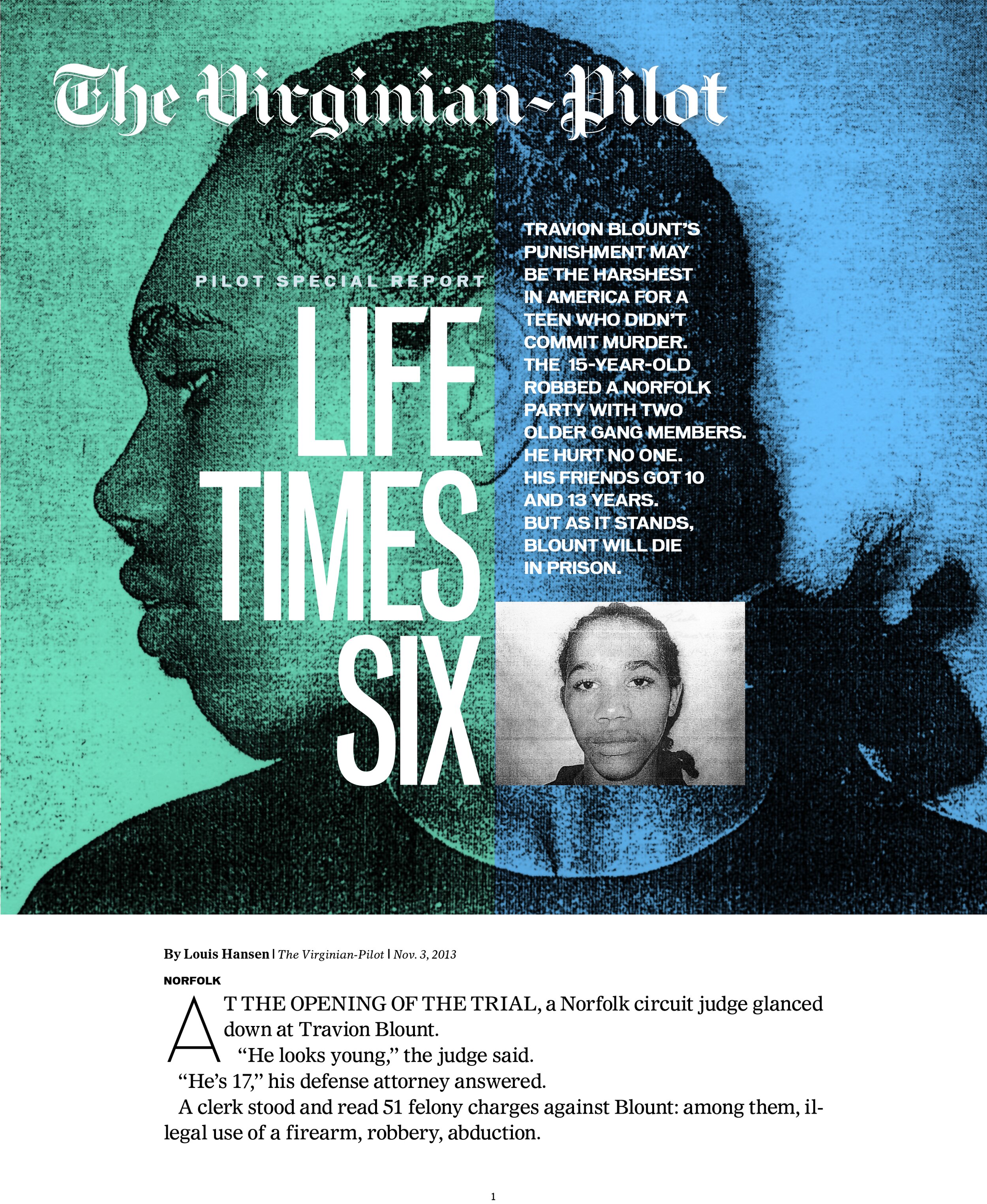

The investigation ran on the Nov. 3, 2013 front page of The Virginian-Pilot, a Sunday. The next morning, it was on Gov. Bob McDonnell’s desk.

Friends and allies emerged -- at powerful law firms, prison advocacy groups, among lawmakers and community and church leaders. I wrote more stories with new details about his appeal and the vagaries of crime and justice in Virginia.

In January 2014, McDonnell issued a partial pardon, cutting Blount’s sentence to 40 years. Several more years of appeals, arguments and a swelling advocacy effort led to a second pardon from Gov. Terry McAuliffe, slicing Blount’s sentence to 14 years.

Blount and I spoke a few more times by phone while he was in prison. He told me about excited, sleepless nights after he heard about his first pardon. About the joy of seeing his family during their first visit to Wallens Ridge, a 7.5-hour drive from Norfolk. About his two daughters, whom he’d barely gotten to know. The conversations were more relaxed than our prison meeting. There were no chains rattling in the silent pauses.

In the first few months of 2020, the question for Blount’s family and friends was when, not if, he would get out.

He was moved to a prison closer to home. His family could visit regularly. He took trade and skills training and earned a certificate in custodial maintenance.

He imagined a future.

Blount’s case drove efforts to reform child justice in Virginia. A state Supreme Court ruling changed the way pardons are handled by the governor.

More importantly, two new Virginia laws took hold July 1 granting greater rights to youth defendants.

A juvenile court judge -- not a prosecutor -- now decides whether to upgrade serious charges for those under 16. Prosecutors and defense attorneys present evidence to the court, and a judge, trained in handling family court disputes and crimes, decides whether the defendant is treated as a child or adult.

This gives the system another chance to step back and put the case, and child’s life, into context.

Before, prosecutors had powerful incentives to charge children as adults, where they faced significantly higher punishments. Law and order is popular with voters, and the thinking often is that it’s better to be safe (put a kid in prison) than sorry (give him a second chance and he commits another crime).

Another new law creates a second chance for underage offenders serving life in prison. Any child sentenced to life or say, 118 years, gets a parole review after 20 years, rather than waiting until they turn 60.

At these reviews, one question typically rules: Are you going to be a threat to society?

Maybe officials will also start to ask: How are you a different person today?

Blount was freed from prison in February.

I spoke with him again a few weeks after his release. He was 29, and he’d served 14 years -- less time than expected, more time than his former friends.

He’d made it through the years with the help of his family, Coggeshall and Monique Santiago -- a volunteer mentor and advocate for Virginia prisoners. She’s starting an organization dedicated to helping incarcerated men and women.

Monique Santiago, left, jokes with Travion Blount in her home. She has taken Blount into her home as he transitions from prison to freedom.

Santiago and her fiancé have taken Blount into their Virginia Beach house for a year. She’s helped him reunite with his daughters, found him a new wardrobe and a job and steered him toward healthy habits.

Santiago keeps away toxic friends and family from his past. “We’re not having it,” she said. “I’m the Momma Bear here.”

He’s working full time at a recycling plant, despite getting hired at the beginning of the Covid pandemic. He’s happy for the work and any tasks at hand. “Whatever they want me to do,” he told me.

Most days, Blount sees his teenage daughters. They’re teaching him how to use a smartphone and text. “I’m not used to all these little emojis,” he said, and laughed.

He has a new girlfriend, and they’re taking it slow. He doesn’t yet have a driver’s license.

He’s become a bit of a celebrity, collecting more than 500 messages from as far away as New Zealand and Germany. His face is on t-shirts.

A clerk at a Virginia Beach Walmart spotted him in line and screamed. “I know you!” she hollered. She ran around the register and hugged him.

At the neighborhood Hardee’s, a man behind him waved the morning paper. “It’s you!” the man said, and bought him breakfast.

Blount said he wants to work hard, find an apartment and spend more time with family.

Freedom, he said, “is beautiful.”