A $1.6 million federal grant could unscramble the I-264 ramps in downtown Norfolk. But would it reopen an isolated, Black community?

This story is the first in a series about highway development through Virginia’s Black communities, and efforts to reconnect neighborhoods decimated generations earlier.

By Elizabeth McGowan

Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

NORFOLK, Va.—The red brick apartment building Zenobia Wilson called home for a dozen years was a ringside seat to a noisy, polluting, 14-lane jumble of Interstate-264 overpasses, cloverleaf interchanges and ramps whizzing around the majority-Black St. Paul’s neighborhood.

But when the mother of three moved out of Tidewater Gardens in August 2022, it wasn’t by choice.

Norfolk was advancing another long-simmering initiative to “deconcentrate poverty,” christened the St. Paul’s Transformation Project. Its initial $400 million phase called for demolishing all 618 units of the deteriorating, barracks style public housing. Everybody had to relocate.

Wilson remained dry-eyed while packing the boxes, trash bags and plastic tubs brimming with her family’s worldly belongings into her station wagon and a friend’s car for a series of 3-mile treks to her next home in Diggs Town, another public housing complex.

“When you live in survival mode, you have to adapt way quicker,” the 38-year-old mother of three said. “You don’t have time to think. I just had to go.”

It’s a constant refrain through generations of Black families in Norfolk. And more disruption looms.

Norfolk has embarked on three, massive downtown redevelopment projects expected to again remake and reinvigorate its core: a $2.6 billion seawall project from rising flood and tidal waters, the St. Paul’s transformation from Tidewater Gardens to the new Kindred community, and, most recently, a reimagined I-264 highway interchange funneling traffic into the business district and waterfront.

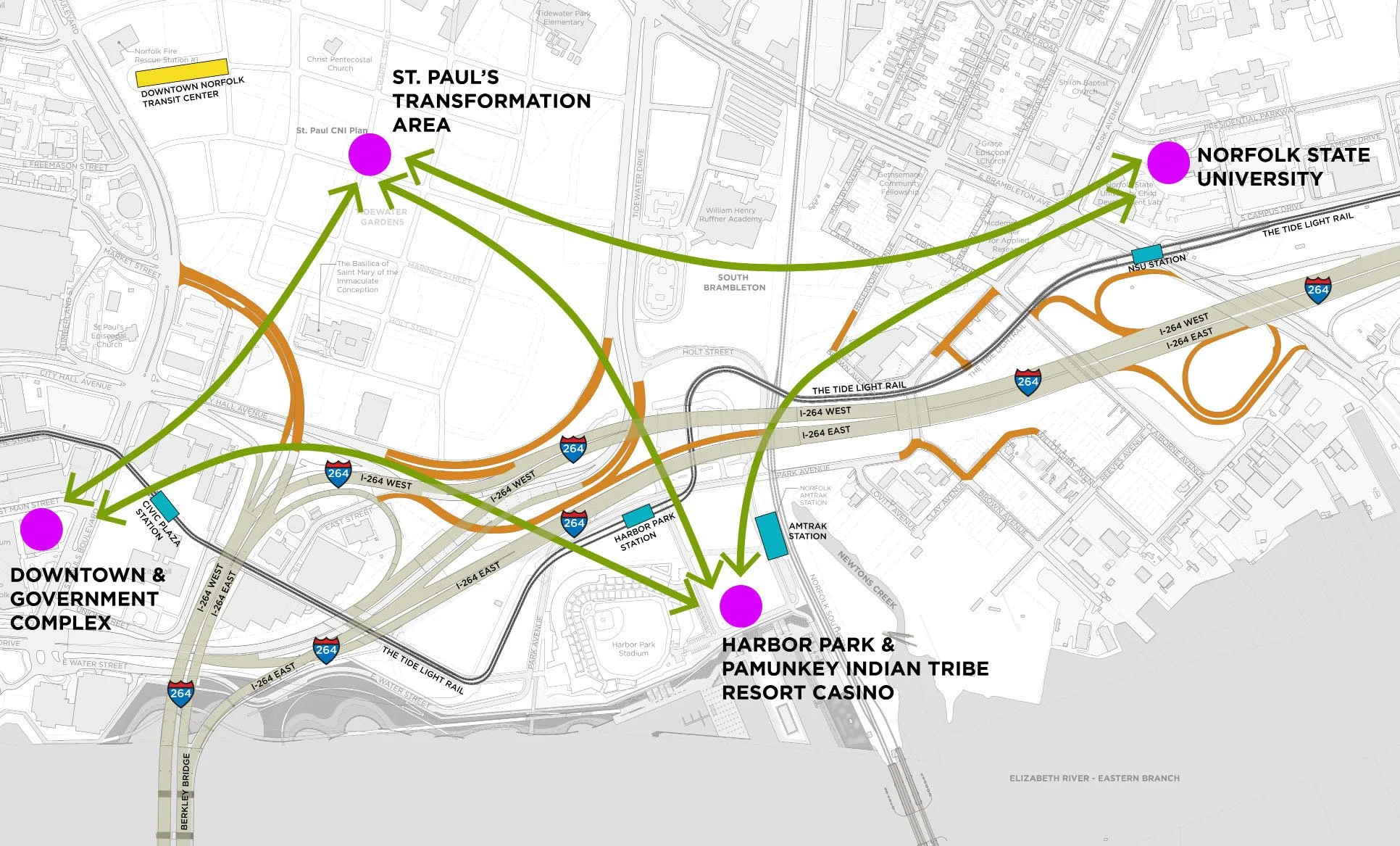

A redesigned I-264 – planned with $1.6 million in seed money from a new federal Reconnect transportation grant - could untangle decades of segregation imposed by interstate construction through Black neighborhoods. It could have a sweeping impact on the vibrancy of long-neglected communities.

But Black community members remain weary of yet another city project designed to improve their neighborhoods. Despite Mayor Kenny Alexander’s public proclamation that reconnecting Black communities is a top city priority, Norfolk has fallen far behind another grantee, Richmond, in planning for the highway redevelopment.

Skeptics also question whether Norfolk’s first Black mayor can undo some of the historic mistakes and disruptions made during decades of redevelopment in the city’s Black neighborhoods.

They worry that reinventing a community near the Elizabeth River waterfront will become a magnet for wealthier, mostly white urban pioneers.

Wilson remembers her grandmother being displaced from a different Norfolk neighborhood, Huntersville, in the name of urban renewal.

“When I hear, ‘This time things will be different,’ I think it’s malarkey,” she said. “They’re saying it’s for us, but really they’re just sprinkling us in there to make us feel welcome.”

A history of disruption

Part of Wilson and other Black residents’ wariness stems from Norfolk’s history of racist policies that author James Baldwin condemned as “Negro removal.”

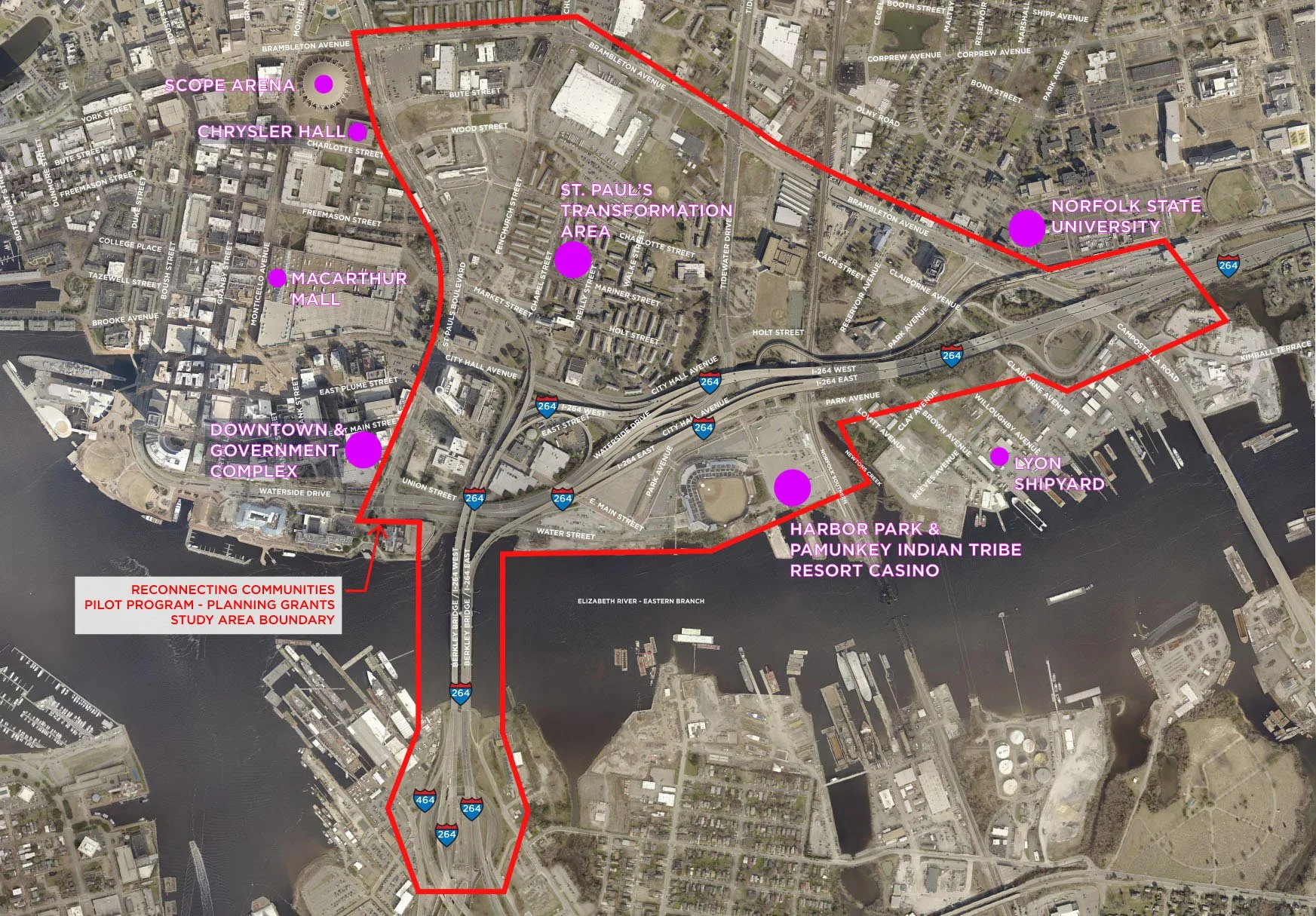

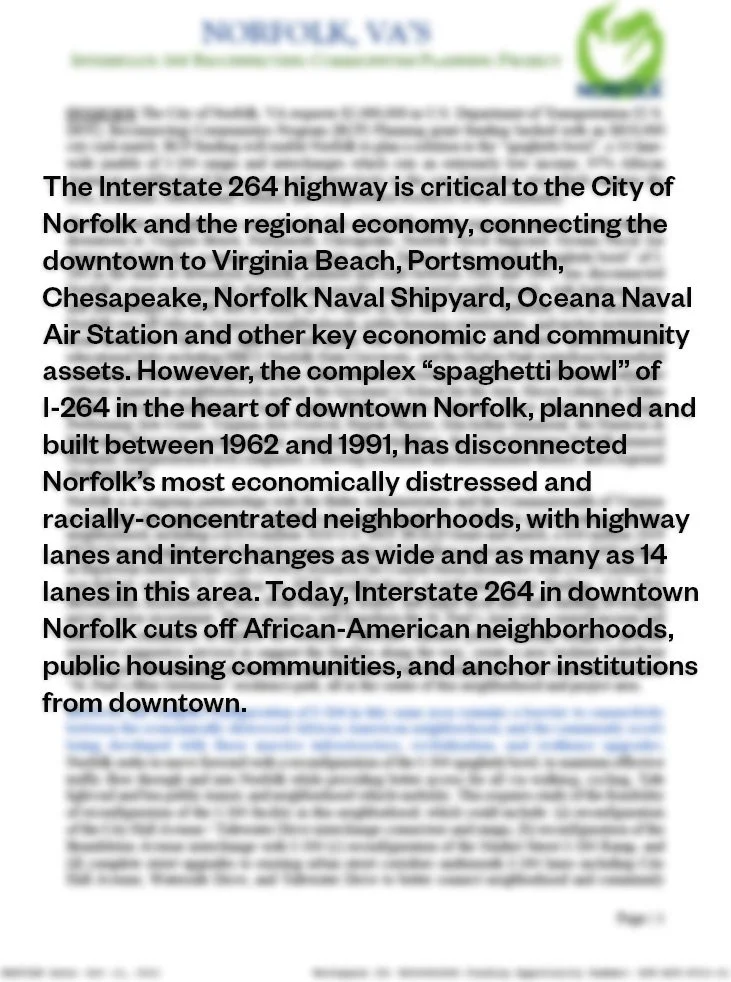

Multi-tentacled I-264 was planned and built between 1962 and 1991 to provide convenient access to Virginia Beach and resources such as shipyards and naval installations. Segments of the “spaghetti bowl” that are dangerous for commuters also intentionally isolated St. Paul’s residents.

Similar 20th century highway projects displaced more than a million Black people nationwide when they tore through urban neighborhoods deemed voiceless and expendable.

Recognizing the consequences of those wrongs prompted the Biden administration to launch the first-ever, five-year, $1 billion Reconnecting Communities Pilot, included in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

“Transportation should connect, not divide, people and communities,” Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg said when announcing the first round of 45 planning and construction grants distributed nationwide.

The Norfolk grant funds planning for a redesigned interstate. City officials can apply for construction money from the same federal Reconnecting source.

In its Reconnecting grant application, Norfolk explained that reconfiguring the I-264 traffic maze could link marginalized residents to jobs, trails, public transportation, retail outlets and other amenities in the city’s prized—and oh-so geographically close—waterfront and revitalized downtown.

Nowhere did it mention how that could actually happen or that the city had already embarked on a massive St. Paul’s makeover with public and private funds.

Norfolk State University professor Cassandra Newby-Alexander said it’s disingenuous to talk about reconnecting what has already been knocked down.

“How is it possible to reconnect when nobody is left in that community to connect with anything?” asked Newby-Alexander, who moved to Norfolk as a child and teaches Virginia Black history and culture. “The city pulled a bait and switch. You can’t reconnect people who are new.”

But city spokeswoman Kelly Straub begs to differ.

“The goal is to benefit former residents who choose to live in the community,” Straub said, “and also new residents who choose to live in the community.”

In a phone interview, Mayor Alexander said the city was still early in the planning process. “I don’t have anything to show and tell with Reconnect. We’re not there yet.

Norfolk lags behind Richmond

In February 2023, Norfolk and Richmond were the sole two Virginia cities awarded Reconnecting Communities planning grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Unlike Norfolk, Richmond’s Office of Equitable Development—at the urging of Black Mayor Levar Stoney—had already coordinated a series of multi-agency sessions and events in 2022 to gather insights and feedback from citizens about the potential of reconnecting Jackson Ward, a historically Black community near downtown.

“Reconnecting Virginia Communities: Has redevelopment changed?

Highway construction ruptured Black neighborhoods nationwide when interstate builders took the path of least political resistance while expanding transportation in the 20th century. Today, Norfolk and Richmond are two Virginia cities vowing to reconnect ruptured communities with federal grants from the Biden administration. But many residents are weary of another round of city promises and uprooting their families. In the first article of a three-part series, the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO explores displacement and gentrification fears in Norfolk as the city embarks on an ambitious plan to reinvent the St. Paul’s neighborhood long isolated by I-264.”

In the 1950s, an asphalt scar that became I-95, bisected the neighborhood once known as the Harlem of the South, displacing 7,000 residents.

Richmond officials have laid out specific proposals to link north and south again by covering a stretch of I-95 with a park-like lid. The largest and most expensive version would offer five new acres of green space for recreation and cultural activities. Discussions about a path forward are still ongoing.

Meanwhile, Norfolk has yet to organize neighborhood meetings and has just begun collecting site-related data. But Straub said it’s unfair to compare Norfolk with Richmond because they may be different projects.

What they definitely have in common is that construction—if it ever happens in either city—is likely years away.

Newby-Alexander is among the detractors wondering if Norfolk is capable of balancing progress on Reconnect with other massive undertakings such as a $2.6 billion floodwall endeavor to protect the city from catastrophic storms with tide gates, levees, pump stations and natural features such as oyster reefs and native vegetation along the shoreline.

But Mayor Alexander remains confident the city has the political will, money and access to the expertise to proceed. At the same time, he added, “I don’t want to leave anyone with the impression that these projects are a done deal.”

The Federal Highway Administration is in the final stages of approving the grant agreement with Norfolk for the scope of the work, an agency spokesperson said. The pending agreement does not preclude the city from moving forward with preliminary planning.

Still, Norfolk is short on specifics for calming and redirecting traffic in its grant proposal. While it won’t conduct a wholesale removal of I-264, officials indicated they would be evaluating at least four trouble spots to smooth access to downtown and part of the eastern waterfront that features an Amtrak station, minor league baseball stadium Harbor Park, the Elizabeth River Trail and, perhaps eventually, a casino.

City planners are focused on the Market Street offramp; City Hall Avenue/Tidewater Drive onramps; two cloverleaf interchanges near Brambleton Avenue; and city streets under the downtown overpass.

“The interstate provides many transportation benefits,” said Norfolk senior transportation program manager John Stevenson, “but it has impacted Norfolk's local transportation network.”

What nobody disputes is I-264’s deplorable beginnings.

The city’s federal grant proposal laid bare Norfolk’s brutal history as a test bed for segregationist policies. It explained how white city leaders counted on residential segregation ordinances, restrictive covenants and “white terror” to advance a racial divide.

“In the 1930s and 1940s, federal government initiatives in redlining and the segregation of defense housing projects validated Norfolk’s discriminatory housing practices and emboldened … leaders to continue to segregate the city,” the proposal states.

Throughout the 1950s, the federal government funded projects that cleared Black neighborhoods deemed “slums,” demolished mixed-race neighborhoods and transformed Black communities into public housing complexes. Buffer zones preserved residential and school segregation.

To this day, majority Black neighborhoods are concentrated on the east side.

“All of this was concreted into place in the 1960s through (the) 1980s when I-264 boxed inequity into these same neighborhoods,” they wrote. St. Paul’s was surrounded by primary urban connectors, “so that others could avoid it entirely.”

A matter of trust

Six months after moving to Diggs Town, Wilson uprooted her family again when a newer, more appealing, condominium opened in the Norview neighborhood, a quicker commute to her downtown store manager job.

It’s on higher ground than Tidewater Gardens, so she doesn’t wrestle constantly with mold and flooding. Still, she misses the nurturing sense of a close-knit community and the nearby fields and a playground where her children could be outside. Now, an asphalt parking spot is her only outdoor space.

The impending loss of her home prompted Wilson to join advocates with the New Virginia Majority, a statewide civic engagement organization. The nonprofit marshaled a campaign several years ago to try to convince the city to minimize displacement upheaval by razing and rebuilding Tidewater Gardens in stages.

Source: City of Norfolk application for U.S. Department of Transportation Reconnecting grant

Disrupting social bonds and scattering residents citywide struck the group’s Norfolk organizer Monét Johnson as an act of bad faith designed to keep them from returning. “The city is just shifting Black people around to make the neighborhood of its dreams,” Johnson said.

Wilson thought testifying before the City Council would change minds.“You get worked up and passionate about something they’re doing that isn’t right,” she said. “We thought that as a group we would have power in numbers and things would change.”

It didn’t alter anything, she said, except lowered her opinion of Alexander, whose campaigns highlight equity as a core value.

“How could you watch a whole neighborhood be displaced and do nothing about it? ” Wilson asked.

That lack of trust stings Alexander, who served in the General Assembly for 14 years before being elected as Norfolk’s first Black mayor in 2016.

“I think that’s an unfair criticism,” Alexander said in a brief interview at an early March city council meeting. “Former residents have a guaranteed right to return.”

Indeed, displaced residents who meet eligibility requirements may move back to the new community for up to five years after their current lease expires, according to a city ordinance.

“When we re-envisioned St. Paul’s, I met with the community, I listened to them,” he said. Alexander pointed out that the transformation initiative has vastly improved residents’ lives by “deconcentrating poverty and strengthening families.”

He cited the city’s $3 million annual investment over five years in the People First Initiative to help residents with the stresses of moving out of Tidewater Gardens. The initiative guides tenants through the intricacies of finding new housing and links them with job training, child care, transportation, schooling, health insurance and other necessities.

NSU professor Newby-Alexander, no relation to the mayor, said that while discourse about “deconcentrating poverty” might sound noble and enlightened, it’s nothing more than a catchphrase.

“We need to be asking who concentrated that poverty,” she said. “Blighted areas don’t become blighted on their own. The city neglected that area for years. That is the behavior of Norfolk.

‘We have learned from the past’

Susan Perry, director of the city’s Department of Housing and Community Development since 2021, has focused on resilience and alleviating poverty in her decade-plus career with local government.

Perry knows the stains of earlier redevelopment projects that bulldozed and replaced Black neighborhoods still linger.

However, she views the first phase of transforming St. Paul’s as an opportunity to undo past injustices—and perhaps begin to heal an ugly racial divide. The next two planned phases are reinventions of nearby Calvert Square and Young Terrace public housing complexes.

The city began meeting with Tidewater Gardens residents in 2018 to gather input about the redevelopment’s roads, building design and green spaces. The housing portion of the redevelopment is funded by a $30 million federal Choice Neighborhoods Initiative grant.

“We have learned from the past,” Perry said. “We’re not just replacing outdated housing and fixing flooding here. We’re repairing years and years of isolation and separation.”

That revamp included re-establishing a surface street grid near Kindred so downtown is reachable, not merely visible.

“We have a ways to go,” Alexander said about that effort, which is entirely separate from any federal Reconnect projects. “I’m not saying we’ve spiked the ball or that we’re going to correct decades of policies that disconnected and segregated, but I think we’re making progress.”

A build-first approach requested by New Virginia Majority and other advocates wasn’t possible, Perry said, because the Choice grant had a strict timeline requiring relocation, demolition and a rebuild by autumn 2025. Also, building anew on such soupy topography meant contractors had to elevate the land by up to seven feet “and that can’t happen when residents are in place,” she added.

As the plan now stands, 216 of the 714 Kindred units would be market-rate rentals, 260 will be deeply subsidized, and another 238 will be affordable, for those earning between 60% and 80% of the area median income. The latter two categories target former residents.

“We didn’t say we need to create a place where millennials can live and gather,” Perry said about the city’s commitment to affordability. “That was not the city’s intention.”

Johnny Finn, an urban geographer and associate professor at Christopher Newport University. Photo by Elizabeth McGowan

Johnny Finn, an urban geographer and associate professor at Christopher Newport University, said earlier projects similar to Kindred attracted mostly higher-income white newcomers.

“I hope I’m wrong and that my pessimism turns out to be misplaced,” said Finn, who has studied the health and environmental disparities resulting from racial segregation in Hampton Roads. “I would love to see this investment by Norfolk pay off in ways that benefits a community that for so long has been disinvested in.”

Finn’s concern is that in 10 to 15 years, landlords and developers will pressure the city to switch subsidized affordable units to market rate.

“It’s one of the biggest current issues in urban geography,” he said. “We spent the entire 20th century disinvesting in Black communities. The way we’re reinvesting seems a Trojan horse for gentrification.”

‘Long time to rebuild trust’

Ben Crowther is the policy director for America Walks, a nonprofit created three decades ago to promote pedestrian-friendly communities nationwide.

While he’s disappointed that Reconnect funding was pared to $1 billion from the originally proposed $20 billion, he believes in the program’s goal to fix past transportation wrongs.

“This is 100 percent a federal problem and reconnecting communities is what the federal government should be doing,” Crowther said. “Dealing with these problems is beyond the means of individual cities and states.”

One drawback to the smaller pot of money is that federal transportation officials are seeking shovel-ready projects to prove the program is in demand and to highlight success stories, he said.

“When you work with communities traumatized by highway infrastructure decisions of the past, it takes a long time to rebuild trust,” he said. “The best projects we see have been having these conversations with citizens for years, if not decades.”

New York state is at the cutting edge of reconnecting advances, he said, pointing to Rochester, Buffalo and Syracuse.

For instance, Rochester embarked on a proposal to replace a piece of the Inner Loop, a sunken highway, decades before Reconnect grants existed. It took from 1990 to 2017 to create a walkable, bikeable community on a mile-long stretch of a surface road flourishing with new housing, retail and restaurants. It has been such a triumph that a second phase is now unfolding.

Crowther offered general advice for cities leading Reconnect projects.

One, think big because that’s how the interstate highway system was created. Home ownership opportunities for low-income residents should be prioritized, he said. Large real estate developers shouldn’t reap all the profits.

Two, start out by walking and talking with residents regularly because their feedback should guide what’s possible. Public meetings should be about listening, not just handing out information.

And three, be transparent, and be willing to alter plans and acknowledge when you’re wrong.

Newby-Alexander said that if past is prologue, she wonders how motivated Norfolk is to engage with people.

Perhaps, she said, the Reconnect grant would be more appropriately spent in a different isolated Black Norfolk neighborhood where the community is still intact—and reconnecting could actually occur. “My question to the city is, ‘Why do your plans always involve removing Black people?”

In search of home

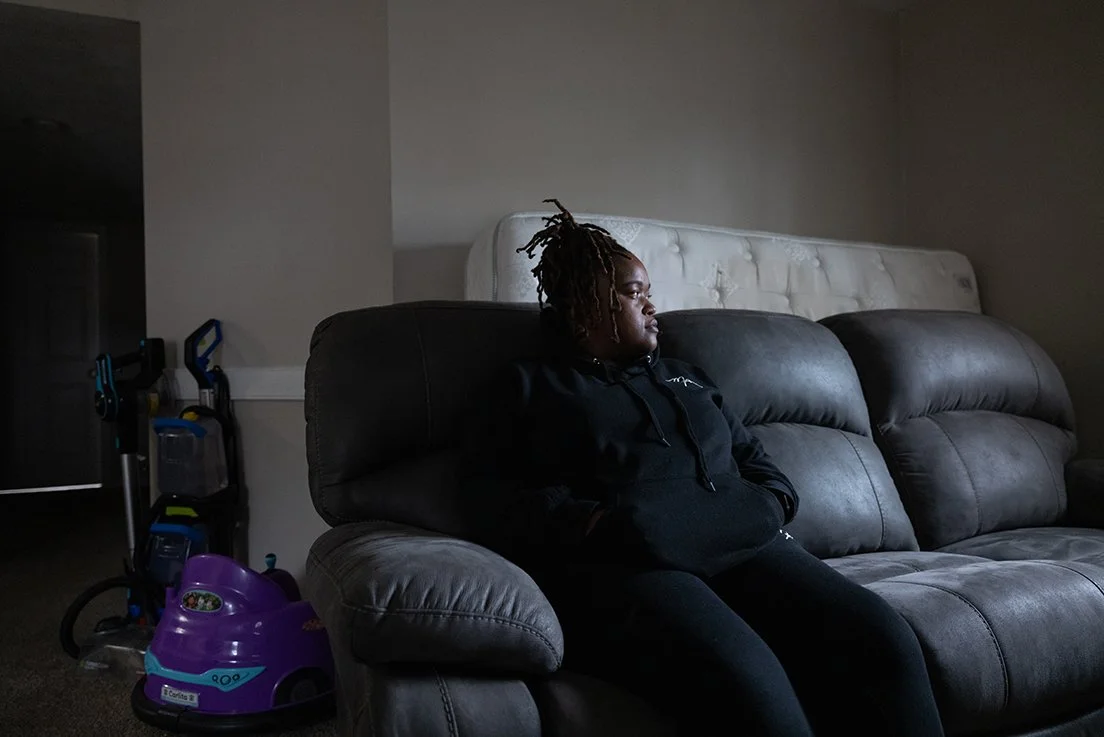

Until a few months ago, Wilson was on the fence about returning to Kindred. For the time being, she is staying in Norview mainly because her 5-year-old and teen-age daughters have settled into higher-caliber public schools, and her oldest, a son, is on the cusp of moving in with his father.

Zenobia Wilson in her Norview apartment. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ

However, that churn of being forced to relocate had the Norfolk native fixating on childhood memories of similar tribulations faced by her maternal grandmother.

When the city reinvented the historically Black Huntersville neighborhood near downtown in the 1980s and 1990s, Ethel Harris ended up at Park Terrace, low-income apartments near Booker T. Washington High School. The retiree couldn’t afford to return to her restored community, known for its landmark Crispus Attucks Theatre.

Those multigenerational stories, Wilson said, forced her to acknowledge a painful truth—her hometown’s pattern of uprooting and dispersing Black residents in the name of progress.

While adjusting to Norview, she hasn’t let go of an objective she has prized for years—trading a housing voucher for home ownership.

“Leaving Tidewater Gardens was bittersweet. I knew one day I would move from public housing, but I wanted it to be one little move and, boom, we would be living in a house,” she said, her voice trailing off. “Maybe I can strive for that, if I stick to a plan.”

Reach Elizabeth McGowan at elizabeth.mcgowan@renewalnews.org

* This story was reported via participation in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 National Fellowship. The Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Journalism provided training, mentoring and funding.