The historic Black neighborhood of Jackson Ward was intentionally split by highway development in the 1950s. Generations later, could a plan to reconnect the north and south sides renew a community?

This story is a second in a series about highway development through Virginia’s Black communities, and efforts to reconnect neighborhoods decimated generations earlier.

By Elizabeth McGowan

The Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

RICHMOND, Va.—Civil rights activist Gary Flowers bowed his head near a scrappy patch of grass hard by Interstate 95 on the north side of Jackson Ward.

“This is sacred land,” he said, gesturing toward what was once 911 N. James St. “My family had a deep rich history here.”

Starting with his maternal great-grandparents, the Fountains, three generations of family lived there—until the bulldozers circled seven decades ago.

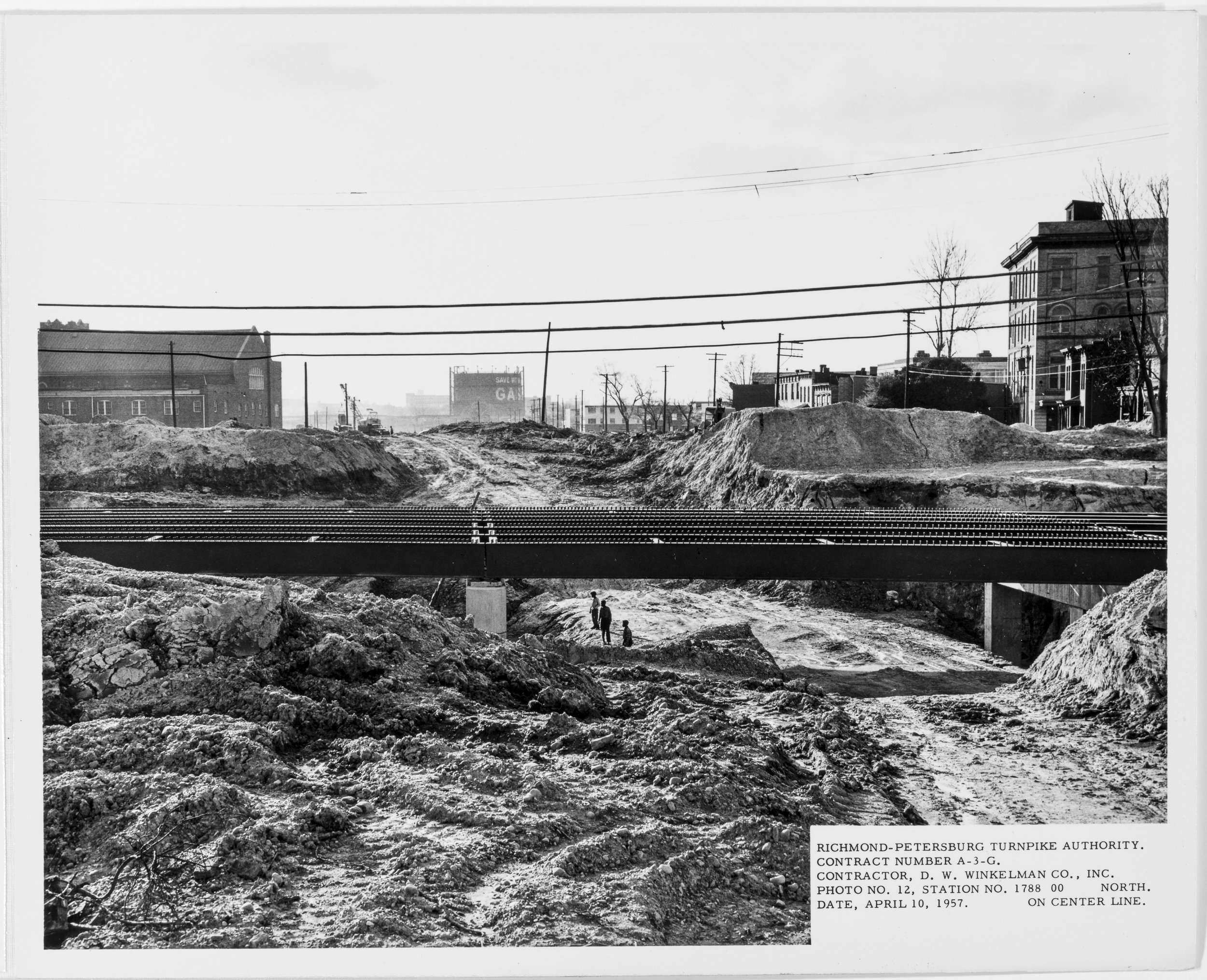

Wrecking balls leveled their 1890s-era clapboard home, along with roughly 1,000 other structures, displacing 7,000 residents to clear a corridor for the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike, which morphed into I-95 by 1958. Intentionally ramrodding highways through Black neighborhoods lacking the political power to halt them was a destructive scenario repeated across America.

Recalling the pittance paid to families who lost their properties to eminent domain infuriates Flowers.

“They dug this ditch out of meanness and greed,” he said, pointing to the traffic-jammed, six-lane asphalt scar.

The fourth-generation Richmonder becomes equally fired up about the city’s newest vision, backed with federal money, to reconnect Jackson Ward by covering a section of I-95 with up to five acres of public green space. He dismisses that proposal as a “glorified doggy park,” claiming the three narrow bridges now crossing the highway are sufficient.

“You can’t reconnect people who were forcibly removed,” Flowers said. “All they’re doing is building new real estate for developers who are salivating to build shiny new housing for young white couples.”

It’s little wonder that some Black residents harbor such searing hurt and suspicions. I-95 is merely one offense inflicted by a white power structure that sanctioned racist policies that enabled redlining, segregation and stagnation.

However, other neighborhood natives view this newest federal project –intended to begin healing old wounds–as a ticket to across-the-board economic prosperity.

“The timing is right to create a new situation here,” said David Lambert, an entrepreneur from a prominent family of professionals. “The problem is that we have too many doubters with a mentality of, ‘No, we don’t want that.’

“We have to be looking at opportunities to rejuvenate Jackson Ward and find solutions that lift everybody up.”

Funding is from a $1.35 million Reconnecting planning grant the city received from the U.S. Department of Transportation in February 2023.

“Enlightened, 21st-century transportation planning and design has to be about integrating any new transportation asset with the surrounding community,” U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg told a smattering of politicians when he toured Richmond before the grant was awarded. “That’s what the future of Jackson Ward could be.”

Richmond and Norfolk are the only Virginia cities to receive grants from the Biden administration’s $1 billion Reconnecting Communities Pilot, included in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Just 45 U.S. cities received the initial planning funds.

It’s the country’s first-ever federal program to aid communities split by highway construction that compounded segregation in cities nationwide. Highway projects in close to 1,000 cities displaced 1 million people between 1949 and 1973, according to research by the Institute for Justice. Two-thirds of the residents ousted were Black, removed from their communities at a far higher rate than whites.

Often, these projects disrupted stable communities and stymied Black home ownership in the name of urban renewal.

In Richmond, fissures have emerged as local government officials and residents figure out how to renew a downtown community, once known as the Harlem of the South, so it’s vibrant and inclusive. Even as leaders removed the bronze parade of Confederate war monuments that stained the city for decades, the question of what an evolving Richmond should look like has stirred fresh debate over past displacement, federal intervention and reparations.

A green bridge to prosperity?

A few minutes’ walk from the site of the Flowers’ family homestead, a towering fence and security gate encircle Eye Que Optical, giving it the appearance of an impenetrable fortress.

Lambert, the proprietor, installed the barriers to deter break-ins near his two-story shop just beyond the North 1st Street bridge. Built by his family in the mid-1960s, it includes several rental units.

The 54-year-old businessman is optimistic that closing the I-95 Jackson Ward divide with a highway cap will be a catalyst, restoring boom times to a north side dominated by a deteriorating public housing complex and a few shabby retail operations.

David Lambert stands on the North 1st Street Bridge that is being renovated as part of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Lambert is hoping that that one day the north and south sides of Jackson Ward will be connected with a land bridge over the interstate. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WHRO

“My business doesn’t thrive … because of where I’m located,” he said about the isolated north side. “It’s like you cross the bridge and you’re in a whole other world.”

Lambert’s sister is first-term City Councilor Ann-Frances Lambert, whose district includes north Jackson Ward.

The siblings’ influence in the neighborhood stretches back to their great-grandparents’ times. Their late father, community leader and eye doctor Benjamin Lambert III, served three decades in the Virginia General Assembly.

Ann-Frances is not opposed to the I-95 cap or redevelopment, but emphasizes that the city “can’t come in here with its shiny bells and whistles without addressing what really went down.”

By that, she means taking the legislative reins to address reparations in Jackson Ward.

“That word makes people uncomfortable, but I’m willing to step up and lead the conversation that this city is ready to have,” she said. “It’s long overdue. We need to rectify the wrongs suffered by those homeowners.”

After 10 years in California, the 48-year-old landed back in the hometown she’d written off—shocked to discover it was on the cusp of a racial reckoning she never imagined.

Levar Stoney, Richmond’s eighth Black mayor had signaled an unprecedented commitment to racial justice four years ago by overseeing the dismantling of Confederate statues along Monument Avenue, erected to signify the post-Civil War “Lost Cause” mythology.

Ann-Frances, who is up for re-election this November, is on edge about Richmond’s progress backsliding when a new mayor is chosen. City rules prevent Stoney from running for a third consecutive term.

Stoney, a Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor, declined multiple requests for comment for this article.

“It’s about momentum. We have to elect someone who will continue to carry the torch,” she said about the five candidates on the ballot. “We can show the world how we are overcoming our racist history and how we are moving forward.”

‘Vision … can change people’s lives’

The economic imbalance between north and south Jackson Ward is stark.

While both “sides” have similar populations and number of households, the north’s unemployment rate is double that of the south. Twice as many families live below the poverty level and median income is barely one-third.

Black residents make up 95% of the north side population and 47% on the south side, where properties are increasingly rented by Virginia Commonwealth University students.

Source //City of Richmond Jackson Ward feasibility study 2022

Watching his optometrist father advocate for the poor prompted David Lambert, a Howard University graduate, to return to school more than a decade ago to become a licensed optician—and reinvent the family business as Eye Que.

“With vision, you can change people’s lives,” he said about collaborating with nonprofits to outfit low-income residents with eyeglasses. “Part of the reason I stayed is to be a presence in the lives of young Black males.”

Over the decades, Richmond has cycled through multiple blueprints geared at revitalizing Jackson Ward. The latest iteration—with a highway cap as its centerpiece—was folded into a master plan the city adopted in late 2020 to guide growth through 2037, the tricentennial of the former capital of the Confederacy.

Lambert, eager to keep Reconnect Jackson Ward plans in the forefront, served on a steering committee coordinated by the Office of Equitable Development. The city organized a series of multi-agency sessions and neighborhood events in 2022 to gather citizen feedback.

The Reconnect themes that emerged over and over? Whatever happens must elevate and expand Black home and business ownership, history and culture.

In a nutshell, Richmond is contemplating three sizes of highway lids. Each one could accommodate features centered on the arts, recreation and contemplation.

Estimated high-end costs for the smallest cap—covering a one-block span between North 1st and South James streets—are at least $100 million. The largest lid, between North 1st and Chamberlayne Parkway, would run upward of $400 million. The medium version, featuring two parks at either end and a gap in the middle, would be at least $200 million.

While the caps wouldn’t be able to physically support residential and commercial buildings, the adjacent land could.

“The intent of the highway cap is excellent, but that’s about aesthetics,” Lambert said. “What nobody is talking about is the economics. The meat and potatoes question is, how is this going to make money?”

Too many Reconnect doubters fixate on gentrification, Lambert said, instead of realizing its potential to be a launchpad for a robust destination neighborhood that doesn’t shunt Black-owned businesses and families aside.

“This project is no pipedream and it gives me hope … that we can connect the city back and take away the stigma,” he said, choking up as he spoke. “Cuz it’s not about Black and white. It’s about we’re all people and we … want to have a thriving city.”

Reparations can advance Reconnect

VCU instructor Jim Smither views an over-the-highway park as an asset for his former neighborhood—as long as it’s paired with an acknowledgement of past transgressions.

“Healing deep cuts of the past doesn’t begin with a steel and concrete deck that’s green on top,” said Smither, an urban planner and landscape architect. “That conversation has to start with reparations.”

Flower vendors set up beneath a brick colonnade of the Blues Armory in Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood, circa April 1957. The thriving community was known as both “Black Wall Street” and “Harlem of the South.” Edith K. Shelton Photograph Collection. V.91.42.44/PHC0039. The Valentine, Richmond, Virginia

The Richmond native, who is white, is well aware it’s a loaded term. But he said reparations are the dramatic act needed to both alleviate the mistrust that has festered for centuries “and cause a cascade of change.”

In this case, he said, repairs could range from cutting a check to families shortchanged in the 1950s to offering low-rate mortgage loans to encourage their descendants to return to Jackson Ward. In tandem, the city should be prepared to offer financial incentives to lower-income residents throughout greater Jackson Ward so growth spurred by Reconnecting doesn’t force longtime renters and owners to relocate.

Such forethought could set the stage for a Reconnect project that the community fully supports, Smither said.

“Gentrification is inevitable, but displacement doesn’t have to be,” he said. “If I’m a poor person and tools are put in place that allow me to rise with the tide, then that’s a good thing.”

Progress on Reconnecting stalled last fall due to city personnel changes and negotiations with the Federal Highway Administration.

An infusion of money from Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam’s administration had allowed the city to get a jump-start on compiling a detailed feasibility study and the 246-page grant proposal it submitted to Buttigieg, said Marianne Pitts, a deputy director in the planning agency.

After months of dormancy, planners and other professionals are again beginning to meet with neighbors about their Reconnect concerns, said Pitts. Those include on-the-ground tours to identify solutions to site-specific problems.

“What we’re looking at now is what are the next steps we need to take to be successful,” she said. “Reparations are part of that conversation. We can’t use federal funds, but we have to consider how, as a city, do we tackle that issue.”

Cars line a row of immaculate row houses along Baker Street in Jackson Ward in a photo taken in April 1956. Today the spot on the north side of Jackson Ward is vacant except for David Lambert’s eye clinic. Edith K. Shelton Photograph Collection. V.91.42.44/PHC0039. The Valentine, Richmond, Virginia

This fall, Richmond will be seeking outside professionals to use Reconnect grant money to conduct an array of studies that evaluate the impact of a highway cap. They range from the routine— environmental assessments and traffic analyses, to the complex—engaging community members, and researching local history and culture.

For instance, the University of Richmond’s Department of Geography, Environment and Sustainability’s Spatial Analysis Lab, has already embarked on one history project. By transcribing U.S. Census data from the 1950s, the team matched names to the thousands of Jackson Ward residents whose lives were disrupted by I-95.

As is the case with Norfolk, Richmond would be eligible to apply for a federal Reconnect construction grant if the city opts to proceed with its plan.

Exposing hidden history

The Hippodrome theater circa 1959. Scott L. Henderson, photographer. Independent Order of St. Luke Photograph Collection. PHC0016/V.88.20.21a. The Valentine, Richmond, Virginia..

Jackson Ward’s pivotal role in shaping the African American experience inspired Flowers, an amateur historian and host of a nationally broadcast radio show, to capture that context via walking tours.

What began as a settlement of European immigrants and free and enslaved Blacks became a destination point for Blacks after the Civil War. By 1871, Richmond designated Jackson Ward as a new sixth voting district, specifically to contain a burgeoning Black population.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, left, Jack Dabney and Jesse Owens. Robinson, a Jackson Ward native, was a celebrated dancer and actor. The Valentine, Richmond, Virginia.

Over the ensuing decades, the ward became a Black city within a city because Richmond enforced innumerable race-based laws and regulations. Home to 500-plus businesses, seven insurance companies and six banks, it became a happening place also packed with churches, theaters and other cultural establishments.

Richmond’s Black Wall Street is just one moniker of the 20th century’s first half reflecting the diligence, intellect and shrewdness of the people who flocked to an area set aside to isolate them. Flowers’ tours on the south side of I-95 highlight landmarks and resident luminaries of that heyday.

His narrative includes anecdotes about dancer and actor Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, attorney and newspaper publisher Gilpin B. Jackson, and entrepreneur Maggie Walker, the first Black woman nationwide to charter a bank. From its opening in 1903 until 1920, Walker’s St. Luke Penny Savings Bank provided 600-plus mortgages to local residents.

Robinson performed at the Hippodrome Theater on North 2nd—a street later nicknamed The Deuce—where venues attracted entertainers such as Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Ray Charles, Nat King Cole and other entertainers.

Quality Row, the east 100-block of Leigh Street, attracted the wealthiest families, including Walker and her husband, Armstead, a brick contractor. Their home is a museum and national historic site honoring Maggie’s dedication to advancing civil rights, economic empowerment and education to Jim Crow-era Blacks.

Gary Flowers ends his tour with a stop at the plaza celebrating the historical contributions of Maggie Walker, the first Black woman to charter a bank in the United States. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WHRO

From his starting point at the castle-like Black History Museum— housed in the oldest Virginia armory expressly built for African Americans—Flowers was animated as he strode from one feature to the next.

“I compare what happened here to the movie Hidden Figures,” he said about the 2016 film portraying the role three Black female “computers” played in the NASA program during the early 60’s. “The contributions of those three brilliant women were covered over by a false narrative that only white men were smart enough to be astronauts.”

“Jackson Ward has its own deliberately-hidden history. Those stories need to be told.”

Reconnect to what?

Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church, at left, was spared demolition during the construction of I-95. Gilpin Court, a public housing community is at right. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WHRO

When Benjamin Ross looks north across I-95 from a back window in Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church, one question springs to mind.

“My reaction is, reconnect to what?” asked the 71-year-old church historian, surveying a bleak stretch of vacant lots, empty houses and a tiny convenience store with a bulletproof shield at the checkout.

Ross is not alone in perceiving the highway cap—which would amount to a massive backyard for the south side historic church—as a welcome mat for the lawlessness they affiliate with Gilpin Court. The dilapidated 781-unit public housing complex predates the fissure caused by I-95.

Crime isn’t Ross’s only concern. The cap also would block a striking image of the church thousands of highway drivers see daily—a sentinel appearing to rise from a massive I-95 concrete retaining wall.

The tale is that the church—which pioneering Black architect Charles T. Russell renovated to its current Gothic Revival style in 1925—was in line for demolition when the Virginia General Assembly defied local citizens’ opposition to highway construction in the 1950s.

Sixth Mount Zion Baptist Church, pictured on the left, during the construction of I-95 in 1957. Courtesy Library of Virginia.

A female congregant, who overheard that news while working as a City Hall elevator operator, alerted the then-Rev. A.W. Brown. The Baptists sprang into action, forcing a curve into the tunpike’s design so as to skirt the sanctuary—barely.

“We are the Gibraltar of Jackson Ward,” Ross said. “Our message was, you have to swing around it.”

Sixth Mount Zion had gained the clout to be heard, Ross explained, because it’s part of a club of revered Black southern churches including 16th Street Baptist in Birmingham and Ebenezer Baptist in Atlanta, where both Martin Luther King Jr. and his father preached.

Saving the church was a bittersweet victory because membership diminished when nearby homes were leveled, Ross said.

“With a cap over the highway, our preservation story would be diluted because the visual evidence would be gone. That’s when history starts to fade away.”

Slow reinvention of public housing

A sign pays homage to famed actor Charles Gilpin, namesake of the public housing community on the north side of Jackson Ward. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WHRO

The fact that the city is on the verge of razing and reinventing 38-acre Gilpin Court hasn’t resonated across Jackson Ward yet—probably because a series of previous proposals amounted to all talk and no action.

Federal authorities are reviewing a blueprint to replace the city’s largest public housing complex, opened in 1943, with a mixed-use, mixed-income community.

Although the redevelopment project is called the Jackson Ward Community Plan, its cornerstone is Gilpin Court. The community, built on the footprint of what was Apostle Town, was named for actor Charles Gilpin, a Black neighborhood native whose theater career took him to Broadway and the White House. RRHA received a $450,000 Choice Neighborhoods Initiative grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2020 to create the plan.

A mural on a building in the public housing community of Gilpin Court accentuates the message sprayed on the wall below it. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WHRO

The blend of 1,900 new homes—1,300 for renters and 600 for buyers—will be energy efficient and landscaped to absorb the effect of outsize rainfall and extreme heat caused by climate change.

Steven Nesmith, CEO of the Richmond Redevelopment and Housing Authority, said he’s adamant that new housing be built in 11 stages over a 10-year span so residents aren’t displaced by demolition. One-third of the 1,300 rental units will be replacement public housing, one-third will be income-restricted affordable and the remaining third will be market-rate.

“We don’t want to re-concentrate poverty,” said Nesmith, who was hired in 2022. “Public housing was created to be transitional housing. Then it became generational housing and that’s a big, big, big problem.”

Last fall, the agency selected a New Orleans-based developer, HRI Communities, to help the city secure money to execute the construction blueprint.

Recreation and transportation are essential pieces of reshaping the area. Plans call for eliminating gaps in sidewalk, transit and bicycling infrastructure so seamlessly that “the highway fade(s) from the foreground to the background.”

Nesmith wants Black-owned businesses at the forefront of the economic revival. To give current residents a fair shake at participating, he has instigated a small-business incubator and programs that teach financial literacy and job readiness skills. Career-related classes, internships and apprenticeships also are available.

The facade of a once-prominent building is held in place with steel and wood beams. The ruin is a remnant of a more prosperous era on the north side of Jackson Ward. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WHRO

“We’re moving forward no matter if Reconnecting Jackson Ward happens or not,” Nesmith said. “When people come to Richmond, we want them saying, ‘I want to go to Jackson Ward.’’

‘We already have a park’

Flowers doesn’t expect to preserve Jackson Ward in a bell jar, but an I-95 cap is the “wrong priority. We already have a park,” he said, referencing the south side’s Abner Clay Park across from the Black History Museum.

Richmond should reject the Reconnect grant because of its potential to dilute, or even erase, the neighborhood’s storied African American history, he said. Instead, the city should procure funding streams dedicated to elevating Black culture, commerce and education.

For instance, he envisions luring Black-owned restaurants, hotels, clubs and other businesses to transform North 2nd Street into a venue resembling pedestrian-friendly Beale Street in Memphis.

Gary Flowers believes that redevelopment money planned for reconnecting the north and south sides of Jackson Ward would be better spent on other revitalization efforts and educational initiatives. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WHRO

He imagines paying tribute to Jackson Ward’s renowned go-getters by setting up specialized schools such as the Maggie Walker micro-entrepreneurship academy, the Armstead Walker vocational training center and the Bill “Bojangles” Robinson ballroom dance institute.

In the 1970s, much of the neighborhood’s south side was named a National Historic Landmark, a rarity for a Black urban neighborhood.

Also, Flowers is on board with the idea proffered by Smither, the VCU instructor, that descendants of families uprooted by I-95 are due reparative enticements, such as low-interest home loans.

It’s a gesture that could begin mending a broken past layered with might-makes-right behavior.

“People say the pendulum swings, but it’s always punishing to the pigmented,” he said. “They always say, ‘This time it’s going to be different.’ Well, in my eyes, it’s never been different in the history of America.”

Reach Elizabeth McGowan at elizabeth.mcgowan@renewalnews.org

* This story was reported via participation in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2023 National Fellowship. The Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Journalism provided training, mentoring and funding.