By Louis Hansen

Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

NORFOLK - John Coggeshall – or “Cog,” as most knew him — played many roles in his 71 years: actor, musician, nightclub singer, occasional political candidate and dogged defense lawyer.

Coggeshall, dressed in red, white and blue for Norfolk candidate Don Williams, draws a quizzical look from a voter.

Photos courtesy of Stacy Apelt, Monique Santiago, Vandy Singleton.

His tireless devotion to one client, wrongfully sentenced Travion Blount, offered a final role: successful crusader for dozens of inmates unjustly trapped in harsh prison terms. He helped change laws — and dozens of lives — in Virginia and beyond.

Coggeshall died June 19. The cause was cancer, family members said. His wife, Aileen, died just months before his passing.

Mourners gathered at the Third Presbyterian Church in Norfolk July 23 to celebrate his life, including former U.S. Congresswoman Thelma Drake, Clerk of Norfolk Circuit Court George Schaefer, law colleagues, friends from Ocean View, and a collection of gray-haired fans from his nightclub days, known as the “Coglodytes,”

From the pulpit, Norfolk activist Michael Muhammad praised Coggeshall for his commitment to justice. “He heard the scripture and the admonishment of the scriptures,” Mohammad said, “to set the captives free and make the wounded whole.”

Stacy Apelt remembered his close friend’s daily upbeat claim that he was “living the dream.”

Coggeshall, he added, “went full speed and enjoyed every moment of it.”

Prisoner advocate Monique Santiago admired Coggeshall’s dedication and courage. “He taught me I could do anything I wanted to do in life,” she said.

But the eulogies tell only part of Cog’s story.

An unlikely beginning

I got to know Cog around 2012, while I was covering criminal justice for The Virginian-Pilot. Cog regularly came up to me in the Norfolk courthouse, grumbling about his cases, prosecutors and judges, or complaining about “The Media.”

I liked him. Along with the wit and crankiness, he cared deeply about his clients. He certainly had stories.

A native Connecticut Yankee, Cog earned a degree from the North Carolina School of the Arts. He started a band, and hit the road in an old school bus, rumbling up and down the East Coast.

The bus broke down in Norfolk’s Ocean View, stranding the group. Cog never left.

For years, he performed pop covers, bawdy sing-alongs and shake-it romps at Hampton Roads clubs and hotel lounges. At the end of his show, he held up a double-sided cardboard sign: “Applause!” and, tossing and spinning it, “Thank You!”

“He was kind of a wild man,” Apelt said. “A total one-man band.”

But the nightclub scene was disappearing in the 1980s. A fan suggested Cog take his performances to another venue – the courtroom. Cog read the law under a Virginia quirk that allows laypersons to apprentice under an attorney’s supervision. He passed the bar on his first try.

It was like acting, he explained to a friend. “If you go to court and act like Perry Mason,” he said, “you’re going to win cases like Perry Mason.”

Cog the Lawyer

Coggeshall became another one of the court-appointed lawyers shuffling between hearings, mostly in Norfolk, to advocate for poor defendants facing the most serious felony charges — malicious wounding, armed robbery, murder.

As we got to know each other, we talked often about his cases, the law, local politics and music, sometimes over beer and chicken wings. We bonded.

He spent years guiding teenage Skyler Hayward through trials and threats as she testified against Norfolk’s Bounty Hunter Bloods. She provided key evidence that led to murder convictions and lengthy prison sentences for the gang’s violent leaders. When Hayward was released after serving her own sentence, shortened because of her cooperation, Cog picked her up at the jail. “I told you I’d get you out,” he said.

Courtesy for WTKR.

Several months later, in early 2013, we started discussing a story about another client – Travion Blount. Blount was just 15 when he committed an armed robbery with two older men. No one was seriously hurt, but Blount refused a plea deal. Prosecutors were merciless at trial. A Norfolk Circuit judge sentenced him to six life terms plus 118 years.

I worked for months investigating a state criminal justice system that sent children to prison for life, with no meaningful chance for release. The story, Life Times Six, captured the injustice Cog had diligently fought for years.

The story was immediately noticed by state leaders. Two months later, in January 2014, Blount won a pardon from Gov. Bob McDonnell.

Cog started taking new clemency cases. Most were men who had been sentenced to life in prison for mistakes made in their teens or early 20s. Over time, they had matured into model inmates ready for meaningful lives outside prison. Yet Virginia laws gave them no hope of freedom.

Cog’s stage and his passion grew.

Cog the Crusader

He saw a chance to change a system he found frustrating and too often crushing poor Black men.

To Cog, “it was more than just a petition,” said one of his clients, Lenny Singleton. When Cog took his case, Singleton was decades into a double-life sentence for a drug-fueled, week-long robbery spree where no one was hurt.

Singleton was pardoned in 2018. Cog immediately hired Singleton and his wife, Vandy, to identify more inmates trapped in the system.

Cog shifted his practice to preparing clemency packages for governors and the parole board. He worked with advocates across the country, drawing support from wealthy patrons also concerned about the injustices in the legal system. And he won. At least 11 men have been set free through Cog’s efforts; another dozen or so are awaiting decisions.

Cog also worked with state lawmakers to reform sentencing laws, winning small victories that give some of Virginia’s more than 30,000 inmates new chances to prove they have earned freedom.

In January, he emailed me that another client, the last of four petitions he filed to the state several years earlier, had received a pardon. “I just got off the phone with him,” Cog wrote. “Four out of four, the last one being four years after the other three. I am content to pass away now.”

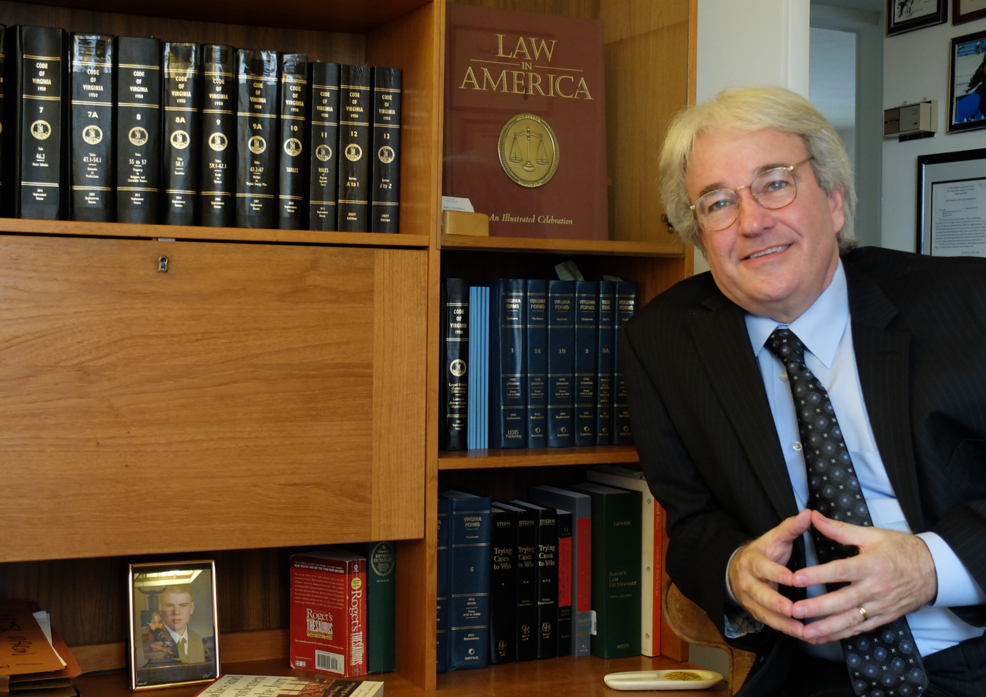

John Coggeshall and his wife, Aileen, lived in Ocean View for decades. Aileen died in February, 2022, four months before her husband.

Was it gallows humor? Cog still pushed hard on new cases. A few recent health problems, including a stroke, slowed but did not stop him.

Coggeshall’s memorial brought out long-time friends and colleagues on a hot summer Saturday.

Blount, wearing a dark shirt and khakis, arrived early at the Norfolk chapel. He hugged Cog’s family, smiled and shook hands.

He settled in the third row. He prayed, and listened and nodded as friends praised Cog.

Eighteen months after his release, Blount, now 31, works full-time in construction, an exhausting but rewarding job. He told me he had a full weekend ahead with one of his two teenage daughters. He planned to take her to an oceanfront water park, and indulge her choices for shopping and movies.

For the first time in his life, Blount has his own apartment, a one-bedroom in Norfolk he started renting in April: “I need,” he said, “my own space.”

To that, Cog would raise the applause sign.

Louis Hansen is senior editor at the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO. Reach him at louis.hansen at vcij.org.