BY CHRISTOPHER TYREE, VCIJ.ORG

SEPTEMBER 9, 2019

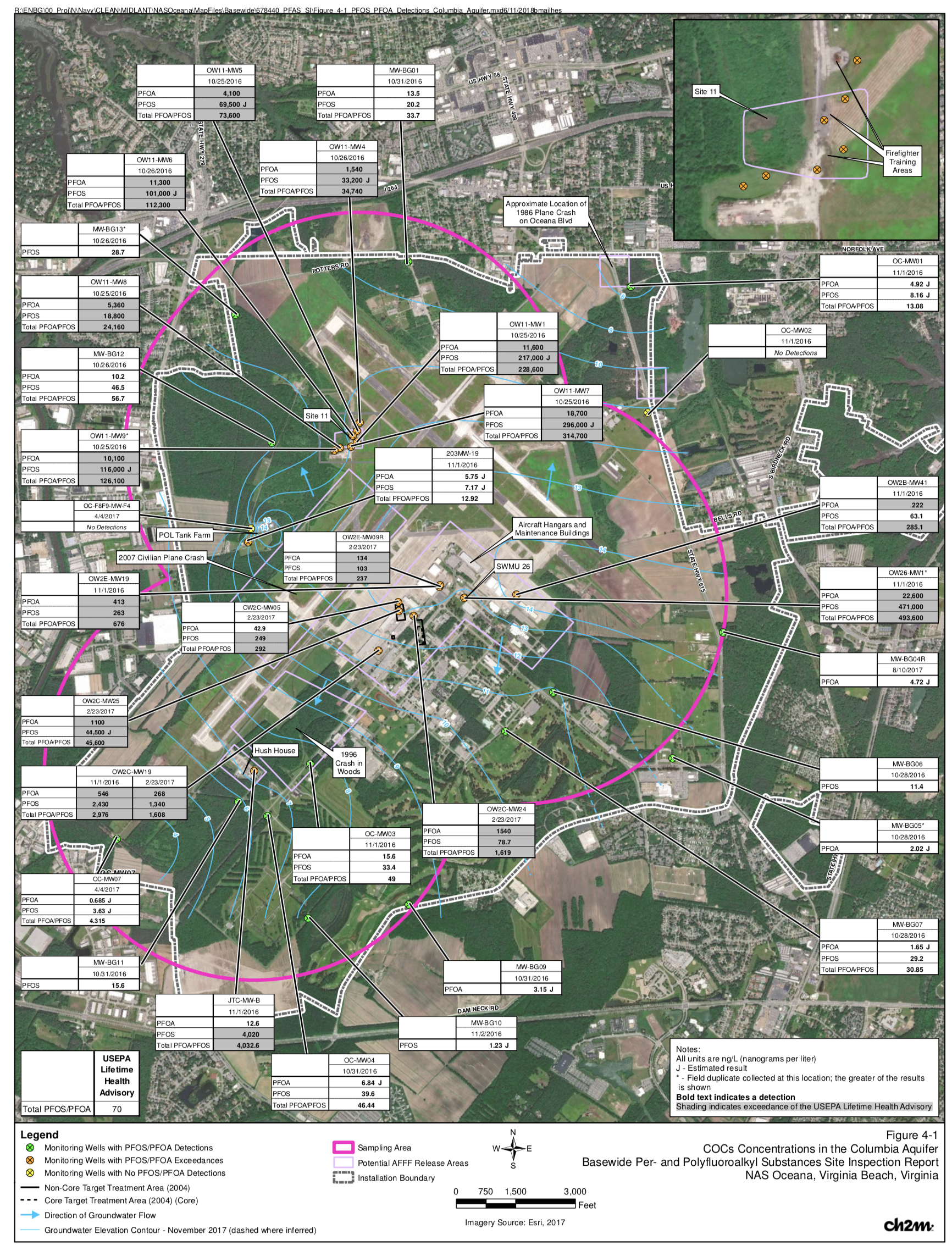

Over 100 wells on and near military bases in Virginia exceeded federal safety guidelines for contamination by toxic, firefighting chemicals used widely in Navy and Air Force training, according to military documents.

The chemicals are found in a foam used by military and civilian firefighters to train and douse high-octane fires for more than 50 years. The foam is still being used, even as the military says it is phasing it out.

The Department of Defense study found elevated levels of the chemicals, known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), in more than 64% of the wells sampled at Norfolk Naval Station, Oceana Naval Air Station, Joint Base Langley-Eustis, and Fentress Naval Auxiliary Landing Field, according to military documents released since March 2018. The levels at one Langley well were among the highest found in the national testing.

The results point to potential risks to residents in several Virginia communities -- Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Portsmouth, Chesapeake, Hampton, Chincoteague and Newport News -- and highlights the challenges the military faces to clean up installations with lingering, toxic threats.

Source: Addressing Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Maureen Sullivan, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Environment, Safety & Occupational Health), Congressional testimony, March 2018

*The Environmental Protection Agency set a lifetime health advisory (LHA) for human consumption of PFOA and PFOS at 70 parts per trillion (PPT).

**These numbers represent the concentration of PFOA and PFOS found in the monitoring wells above the EPA’s LHA.

These man-made chemicals, which contain a string of eight connected carbon molecules strongly bonded together with fluorine, are persistent in the environment, lasting for generations and perhaps even longer. The substances also accumulate in the food chain as animals are exposed.

Exposure to the substances has been linked to testicular and kidney cancers, thyroid disease and pregnancy-induced hypertension, according to an independent study.

The Navy and Air Force say they have taken steps to address PFAS contamination from the firefighting foam -- known as aqueous film forming foam, or AFFF -- at Virginia bases. Spokesperson Alton Dunham, deputy director of public affairs Navy Region Mid-Atlantic, said the Navy is conducting long-term response actions to PFAS in compliance with Environmental Protection Agency and military standards.

The regulatory standards require the Navy to clean up hazardous waste sites at active and shuttered bases, as well as remediate hazardous materials used in emergencies or spilled accidentally.

PACIFIC OCEAN (June 22, 2013) Sailors scrub the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN 73) after an aqueous film forming foam (AFFF) system check. George Washington and its embarked air wing, Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 5, provide a combat-ready force that protects and defends the collective maritime interest of the U.S. and its allies and partners in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Michelle N. Rasmusson/Released) 130622-N-XF988-132

Map of Oceana Naval Air Station showing the location of monitoring wells and the results from testing those wells for PFAS contamination.

“The Department of Navy is committed to identifying and evaluating, and remediating contamination resulting from AFFF such as PFAS.” Dunham said.

The Navy also expanded its testing of private wells around the base last October. It says the City of Virginia Beach’s public drinking water system has been tested and no traces of the substances were found. The majority of homes and businesses around Oceana receive city drinking water.

The military completed a preliminary assessment of the joint base, and will conduct mitigation where elevated levels could pose a risk to humans, according to congressional testimony.

A spokesperson for Joint Base Langley-Eustis declined to comment at this time.

Investigators tested 54 wells near Fentress Naval Auxiliary Landing Field and found seven tested higher than the EPA’s recommended lifetime health advisory level, or LHA, for PFOA and PFOS. Only one of six off-base wells near Oceana revealed PFAS contamination, with a level below the LHA. The Navy has provided alternative drinking water for Oceana and Fentress, and plans further remediation efforts, according to testimony.

The substances have even tainted the drinking supply for 3,000 residents of the Eastern Shore town of Chincoteague, which draws water from wells on NASA’s Wallops Island. Four of the seven Wallops Island wells tested higher than the EPA’s lifetime exposure guidelines. NASA is developing a comprehensive plan to address the contamination. In the meantime, the space agency is supplementing Chincoteague’s water supply with reserves from its own wells. NASA also plans to establish a treatment system to filter water from Chincoteague’s shallow wells.

Scientists examined the potential health dangers of PFAS contamination after community members in the small town of Parkersburg, WV filed a class action suit against DuPont in 2001. The suit charged workers and nearby residents suffered health problems after they drank PFAS-contaminated water used during the manufacturing of Teflon. Dupont settled in 2004 for $70 million and agreed to fund a comprehensive study of the effects of PFAS exposure. The study, completed in 2013, examined nearly 70,000 people and found that these man-made chemicals may have been linked to a number of diseases found in the community -- including ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, testicular and kidney cancers, and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Subsequent studies by federal researchers suggest certain types of PFAS may affect prostate, kidney, thyroid and pancreatic functions, and contribute to high cholesterol, infertility, and inhibit child development. In 2016 the EPA set a non-binding lifetime health advisory for PFAS at 70 parts per trillion, about the equivalent of one drop of this chemical in a swimming pool that would be more than 40 feet deep and 100 yards long. In February, acting EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler announced that the agency would take the first steps toward setting a drinking water limit for two types of PFAS under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Dr. Linda Birnbaum, a toxicologist and director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at the National Institute of Health (NIH), believes the EPA guidelines should be 700 times lower. “We have data and we have evidence that much smaller exposure results in any number of toxic side effects,” she said during an interview with VCIJ. “When you talk about synthetic chemicals, this is the biggest issue of the 21st century.”

Grimy and exhausted, crewmen of USS Forrestal and her airwing continue firefighting efforts in the aftermath of the blaze that killed 134 of their shipmates 29 July 1967. The ship was on station off the coast of Vietnam. In the background are what remains of a row of F-4B Phantoms that were parked along the starboard stern quarter. (Navy released image.)

The Navy began requiring all vessels to carry the firefighting foam after a fire aboard the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal killed 134 sailors in 1967.

The substance was so effective at knocking down jet fuel fires that AFFF was eventually deployed at more than 90 civilian airports and oil refineries around the country.

The foam was widely used at Hampton Roads bases in the 1970s, and was routinely sent into local waterways, according to military reports -- despite warnings from scientists suggesting possible environmental effects. A 1978 environmental impact statement written by the Naval Ship Research and Development Center found that the Navy was discharging thousands of gallons of AFFF into the harbor. The Navy estimated that Norfolk Naval Station released more than 8,000 gallons annually into Willoughby Bay, and Little Creek Amphibious Base sent more than 2,000 gallons into Little Creek, near civilian populations in Norfolk and Virginia Beach.

Recently, some states have tightened guidelines for PFAS levels in drinking water. In March, the state of New Mexico sued the Air Force over contamination.

Virginia is waiting for guidance by the EPA before considering new measures, said Virginia Department of Environmental Quality spokeswoman Ann Regn.

But some long-time Virginia residents are concerned about their exposure.

“During my 28 years with the Department of Defense, the majority of my contact with AFFF is without benefit of adequate personal protection equipment.”

— Timothy Putnam, civilian fire fighter, Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story

On any given day in the 1990s, you could find Timothy Putnam and his firefighting colleagues washing their fire trucks with AFFF at Oceana Naval Air Station, he said. “We were told it was just heavy dish soap. We were never educated on what was in the foam,” Puttnam said in an interview.

Putnam, a civilian firefighter at Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story, testified before a Senate subcommittee in March that the chemical was still used but under heavier guidelines by the Department of Defense. He told senators he used AFFF at most of the military air bases around Hampton Roads.

“While engaged in operations utilizing AFFF, firefighters are regularly exposed to toxic PFAS,” he testified. “During my 28 years with the Department of Defense, the majority of my contact with AFFF is without benefit of adequate personal protection equipment.”

Senator Tim Kaine, D-Virginia, said in a statement he is aware of the issues. “My colleagues and I are working on the Senate Armed Services Committee to ensure the military addresses the devastating effects of water contamination and uses safe materials to fight fires going forward,” Kaine said.

Putnam had another request for the panel: Stop the military from using the toxic foam. “We know that regular exposure to AFFF causes PFAS to present in a firefighter’s blood and tissue where it can remain for years and build up to concentrations that may cause health effects,” he testified. “As we learn more about the toxic impact of PFAS, we must take steps to reduce firefighters’ exposure and protect their health.”