By Philip Shucet

Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

Dave Covington always knew he would be an engineer. His father put in 40 years at the Virginia Department of Transportation. His uncle was a branch chief for NASA at the Kennedy Space Center.

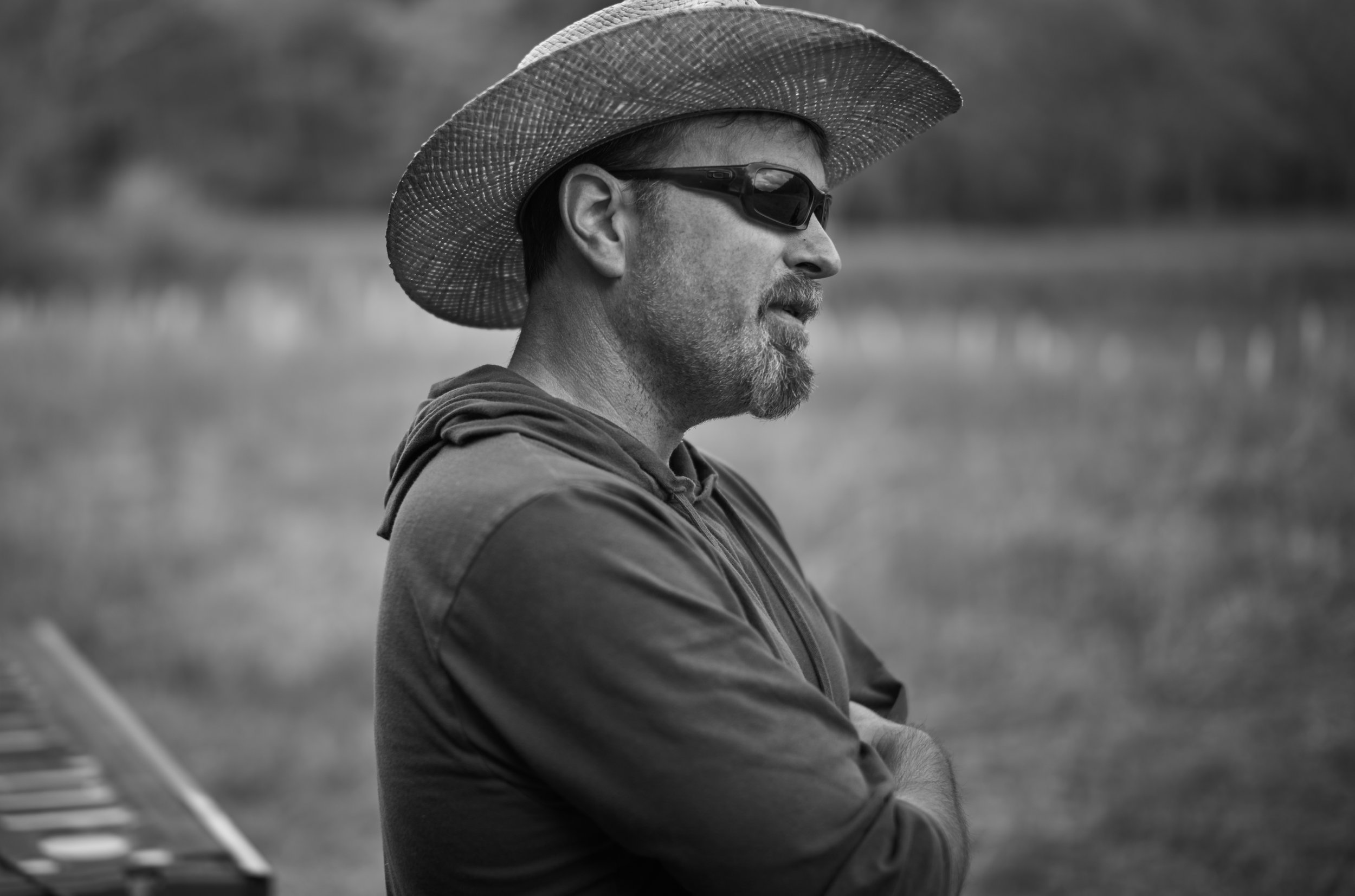

After college, Covington worked as a consulting engineer for 16 years. In 2014 he joined VDOT. Today, he is a program director supervising more than $2 billion of road and bridge improvements on 325 miles of Interstate 81. On the job, Covington relies on sophisticated technology and tools. But on his 107 acres in Highland County, where there is only a 10 x 12-foot cabin, Covington looks for a simpler life. One where work is more meaningful than his job. It’s a philosophy of life that he wants to pass along to his daughter.

Covington, 46, lives in Stuarts Draft. He spoke to us in a studio and again on his land in Highland County.

The interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

This goes back a long way probably, I wanna say somewhere around 10 or 12 when I understood what (engineering) meant. I grew up in a family with several engineers and it was kind of a path that I picked really early in life based on what I witnessed with my father, who was also an engineer, and my uncle who was an engineer, worked for NASA.

I do recall my father taking me on a couple of projects. The Varina-Enon Bridge (across the James River near Richmond) was one that he took me on while that was under construction. That was pretty amazing to me at that young age to see something that massive. I think the primary emotion was just … it made me feel small and made the project seem kind of larger than life.

Strangely, I don't know why, but in my mind, probably by the time I got to high school, my decision was made. I was going to Virginia Tech and I was going to go into engineering.

I guess I’ll start by saying that I feel pretty good about it now, which is ironic because I always swore I would never work for VDOT. I didn’t want to be the guy following directly in his father’s footsteps. I didn’t want to hear, ‘Oh, you’re here because you’re Buster’s son.’

My perspective on it has changed immensely. Immensely. You know, my vision of this when I was young, 10, 12 years old, through college, I just had this vision of I'm gonna be sitting in a cube or an office and I'm gonna be designing things and that's what I'm gonna do with the rest of my life. I landed a job in the Richmond area with Michael Baker (consulting engineers), close to a 10,000-person company. Because I was working in Richmond, it was a much smaller shop, probably fewer than 30 people in the office.

It's so different now than what I ever envisioned. It's better. It’s better, because I always tell people my worst nightmare is being stuck in a room full of engineers. It's true. We are myopic, we see things one way and everything has to have a calculation behind it. But that’s not how the rest of the world lives.

I love construction. I love seeing a new bridge built or a new lane installed on the interstate. I don't really think of myself as an engineer anymore. I think it does very much contribute to who I am. My wife would tell you that. My daughter would tell you that. There's no question it's shaped the way that I think. I certainly would not say that the work that I do for my job defines me — at all.

My job is one element that kind of helps to create the whole picture. Ten percent maybe? Maybe 20?

It had to be the early 2000s and for whatever reason I said, I need to buy some property. I need to buy some land, because I've always been an outdoor person. I've always been a hunter and fisherman, and I like to be alone in the outdoors.

It took me several years before I actually found what I was looking for, and I found that in Highland County, Virginia, which is the least populous county in Virginia. I think that my first parcel was like 57 acres. Looking back on it today, I'm so thankful I did that. I ended up buying the next parcel beside it (50 acres) and that's where I'll eventually live.

There’s nothing there right now. After I leave this work — my job — I’ll work harder after retirement than I did before.

I'm a primitive engineer when I'm out here (on my land). It's all about solving problems, and the stakes are higher. I've had instances out here that could have been life threatening. But I know how to navigate this environment, so I don't really think in terms of engineering out here. But I can't get rid of it. It's still part of who I am. I'll make a tool if I need a tool out here, you know, make it out of wood or stone or whatever it is to get a job done. Is that engineering? Kind of.

We're working toward building a timber frame house. And one of the things that I'm interested in — because I'll have to clear roughly three to five acres of land to build the house up on the mountain anyway — is making use of that wood and maybe integrating that wood into the home. So I'm doing a lot of research. One of the things that I've wanted for the past 15 years is a sawmill, and I think this might be the perfect opportunity for me to justify the investment in a sawmill and to potentially saw the timbers, or at least some of the timbers, for the home.

But I've done a lot with that little ax right there and a small fixed blade knife. I could spend half the day just coming up with little different inventions to make my life a little easier out here.

Dave Covington’s daughter, Everley, 7, sits on the door stoop of their primitive cabin in Highland County.

I could tell (my 7-year-old daughter Everley) about this and it wouldn’t mean much. But if she lives it and experiences it…

We’ll be here tonight. We’re staying overnight. We have no electricity, we have no running water. Our lighting is with oil lamps. I’ve got four lamps in here; that’s my light source for this place.

In some ways a job is a means to an end. And that's very true for me. I mean, I could not have bought this property without a good job and good education. I do enjoy what I do, but at the end of the day, if I had to pick one or the other, I wouldn’t pick my job. I would pick living here, maybe more primitively than what I'm planning.

Living here you’re immersed in work. The work never runs out.

I was very fortunate that my father impressed upon me his work ethic. I hope I have this opportunity to do the same for my daughter, but if you go through life and you don't put in work and you don't produce anything, what is the example that you're giving to your children? You know, without work, what are you, what are you doing?

My job now really is to impress upon my daughter a good work ethic so that she goes out and does good things in her life. What happens for me from this point forward, I don't know that it's irrelevant, but I think once I accomplish that first goal of teaching my daughter how to become productive in society and contribute to a better world, then I can go raise cows.

I'll give the engineering definition of work. Force applied over time — or excuse me, force supplied over distance. But time is a distance. So in my mind, if you stop working, you don't have much distance left; you don't have much time left.

Working Virginia is a monthly series by Philip Shucet. You can reach him at: philip.shucet@philipshucetphotography.com Words and pictures ©️Philip A Shucet.