A Virginia university wanted property for dormitories and classrooms. It targeted a Black neighborhood at the center of the Civil Rights Movement.

By Louis Hansen

Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

FARMVILLE, Va. - In the segregated South of the 1950s, the triangle was home to Black professionals, craftsmen, business leaders, ministers, educators and entrepreneurs. Dozens of children filled the schools and the playgrounds.

The 14-block neighborhood was bound by three major streets: High, Ely and Main.

At one end sat Moton High, the public school for Black students with conditions so poor and dangerous they sparked protests that would mark a turning point in the civil rights movement.

Adjacent to the neighborhood was all-white, all-female Longwood College, which trained generations of Virginia’s school teachers, dating back to the 19th century.

In this aerial image from the 1960s, Longwood College sits in the middle of the frame. At top of the frame is the triangle, a Black neighborhood targeted by the college for its expansion.

In the post-World War II baby boom, Longwood wanted more dormitories, classrooms, and a larger campus for its growing student population. College and city leaders drew up plans to expand the campus. Their target: the Black neighborhood.

Longwood bought prime properties, sometimes using the power or threat of eminent domain – the government’s right to forcibly purchase private property for public use.

Black homes and businesses started to vanish in the triangle. It was a slow change, not always noticed by the children who grew up there.

“I was too young to know about the negotiations taking place,” said Jackie Reid, a Farmville native whose family business bordered the triangle. “I just knew that people…families started disappearing.”

It took years for Longwood to acknowledge its impact on the Black community, another wound to their neighbors. Andthe reckoning continues.

The Moton Museum, once the segregated high school for the Black community and site of the landmark 1951 student walk out, sits in the elbow of Griffin Boulevard and South Main Street in Farmville. The area where the university’s ball fields and parking lots sit was once a vibrant Black neighborhood. Source // Longwood University 2013

Conservative attacks on university diversity, equity and inclusion programs have chilled discourse, forced out presidents and threatened institutions with the loss of billions of dollars in federal funding. The Trump administration has ordered the removal of references to slavery and racism from federal historical sites.

In Virginia, the administration targeted leadership at the University of Virginia, forcing out President Jim Ryan, and launched an investigation into George Mason University President Gregory Washington.

Despite these attacks labeling universities as liberal bastions, public institutions in Virginia and around the country have a dark history – carving away Black neighborhoods in the name of educational progress.

Aggressive campus expansions, most beginning after World War II, robbed many Black families of lives in a stable community and the ability to accumulate wealth through home ownership. Virginia lawmakers formed the Uprooting Commission in 2024 after a series by the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO and ProPublica exposing decades of public colleges targeting established Black neighborhoods for campus expansions.

Campus expansions at the University of Virginia, Old Dominion, and Christopher Newport universities led to the displacement of hundreds of Black families.

Longwood University Provost Larissa Smith stands in the schools courtyard in August 2025. In the distance behind her is the start of the area acquired by the university through the threat and use of eminent domain in the 1960s and early 1970s. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ

In Farmville, Longwood sat at the intersection of civil rights advancement and backlash. School administrators reported to the Virginia Board of Education, unlike other public colleges, and was prone to political influence.

“They very much toed the line with segregation in Virginia and segregation in the public schools,” Longwood Provost and history professor Larissa Smith said. “Longwood wasn't on the fence in the ’50s and ’60s.”

The university has been on a journey to recognize and reconcile its past. It’s been a slow and incomplete process; the wounds run deep. The college’sacquisitions included willing sales and others accomplished through the threat or use of eminent domain, according to school researchers. Between 1966 and 1971, Longwood acquired about 60 properties in the triangle.

Longwood President W. Taylor Reveley IV wrote last year to the General Assembly committee that the school’s actions during the civil rights period affected generations. “Longwood’s actions as an institution, whether directly or by omission,” Reveley wrote, “often had the effect of impeding progress.”

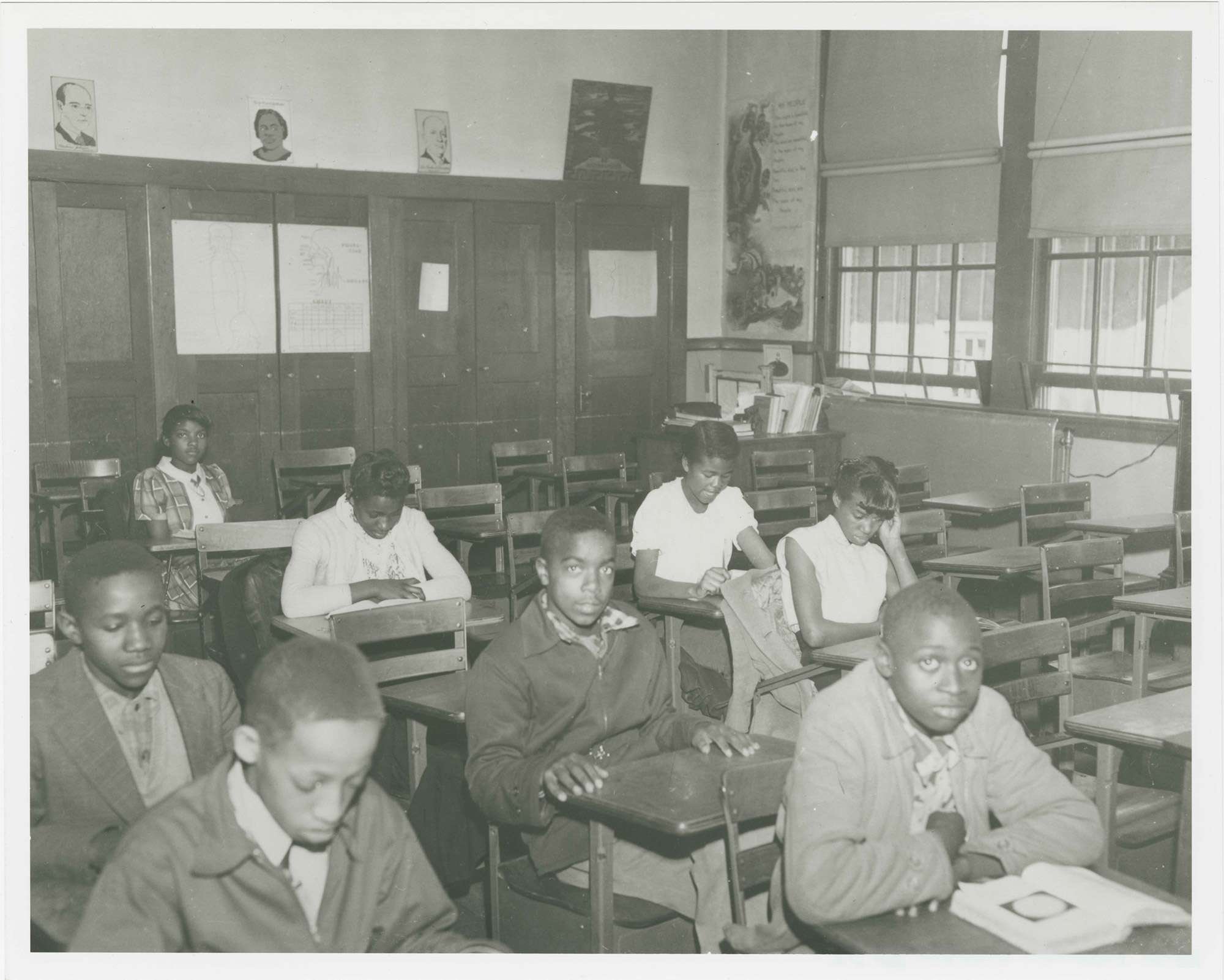

A Moton High School classroom in the 1950s. This photo was used as an exhibit in a landmark federal lawsuit to show the unequal and inadequate facilities Black students faced in segregated schools. Source // National Archives

Longwood College students circa 1960. Source // Longwood University

Jackie Reid has spent all but 18 years of her life in Farmville. Her father, Warren, was an undertaker, entrepreneur and community leader. Growing up in the 1960s, she saw the neighborhood start to change.

Reid, now 71, remembers a thriving community of Black families across just a few blocks.

“There had to be at least 50 children,” she said.

Without video games or smartphones, kids roller-skated, rode bikes and played outdoors. Three major churches anchored the triangle community – First Baptist of Farmville, Race Street Baptist, and Beulah AME. The Elks Hall served as a community hub and dance hall.

Longwood “was totally off limits. Totally off limits,” she said. ”We could go through campus, but we couldn't, like, hang out.”

Chuckie Reid, no relation to Jackie, was the youngest of five children, four boys and one girl. Reid, now 74, said he and his brothers would sled down the snow-covered hills in winter and explore the creeks and underpasses during warmer times. He hung out at First Baptist, doing odd jobs, absorbing the scripture and community activism.

In 1951, Barbara Johns, a 16-year-old student at Moton High School, staged a walkout to protest the deplorable conditions of the school as compared to the white high school nearby. Source // Robert Russa Moton Museum

Farmville became a hotbed for student protests over conditions at segregated Black schools. The student walkout at Moton High in 1951 paved the way for lawsuits that culminated in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education, finding public school segregation unconstitutional.

When Virginia leaders imposed Massive Resistance in 1959, Prince Edward County, where Farmville is the county seat, closed public schools for five years rather than integrate.

White parents sent children to newly established, segregated private schools. Black students were left with a hodge-podge of community-led classes, tutoring, out-of-state and church schools.

Chuckie Reid recalls the years as a child when he was forced out of school by Virginia’s enforcement of Massive Resistance. He is now the the vice mayor of Farmville. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ

“I was 8 years old, in third grade, and I think my mother told me, she said, you know, school's gonna close. So I figured, school's gonna close for like a day,” Chuckie Reid said. “Days went by, weeks went by, months went by. Five years later, I was out of school for five years.”

Reid’s refuge was First Baptist, led by the Rev. L. Francis Griffin. Griffin, known as the Fighting Preacher, hosted civil rights leaders from around the country as they came through town.

Rev. L. Francis Griffin. Source // National Archives

Reid picked up his news from the conversations at church. At home, parents and grandparents talked privately, sharing little with the children. “I don't know if they were mad,” Reid said, “or if they just hurt.”

Many Black people worked as domestics, cooks and groundskeepers at Longwood. But the first Black student wasn’t admitted until 1966, and the first to graduate came in 1972.

While public schools were closed, white community leaders drew up plans to expand Longwood into the triangle. In 1960, the school released a master plan to nearly double the student population during the decade. New classrooms, dormitories, administrative offices and landscaping over several years would cost an estimated $6 million.

Plans called for the purchase of 48 properties in the mostly Black section – including several homes and apartments, shops and a funeral home – over several years. Longwood estimated the purchases would cost about $200,000 – roughly $2.2 million today.

Then-Gov. Mills Godwin pressured Longwood officials to more quickly acquire land and build new facilities, backed by $2.7 million from the state.

In May 1967, the college president, James Newman, complained that Black residents, reluctant to leave their homes, had hindered campus development. Soon after, the Board of Visitors fired Newman. Campus projects pushed forward.

That year, Race Street Baptist Church was condemned through eminent domain, purchased for $18,000 and razed. Between 1966 and 1971, the college bought up about 60 properties in the triangle.

The fight to save homes in the community was a secondary concern, said Skip Griffin, the preacher’s son who grew up in the neighborhood. Most people could not have afforded the time or money to fight a legal battle against the state over eminent domain.

“In another time and place, we might fight this,” Griffin said, “but the real battle is for the schools and for the dismantling of segregation.”

Between 1911 and 1991, Longwood acquired 11 properties through eminent domain, according to university research. The tool was used to take properties from both Black and white owners, and its threat encouraged others to sell.

The Black community pushed back against another expansion plan in 1989. A Black resident told the Farmville Herald the community was aware of the college’s importance for the local economy. “We want jobs, but we want houses, too. We don’t want it to be one-sided.”

At a speech for Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2004, Longwood President Patricia Cormier vowed the school would never again threaten or use eminent domain to acquire property.

It was a prominent public recognition of how the school had treated its Black neighbors, Smith said.

The university continued to evolve and expand. In recent years, it has acknowledged and supported the retelling of Farmville’s central role in the civil rights movement. Its support for the Moton Museum in the preserved former high school allows students and researchers to see and hear the stories of the struggle for equality.

The Black and white public schools being shut down, Smith said, “really did have kind of an incredible, lasting impact on this community, both Black and white citizens.”

Longwood has granted honorary degrees to members of the lock-out generation. It’s compiled research about the impacts its growth and ambition have had on the Black community.

Last year, the university president submitted that research to the state Uprooting Commission. The panel is collecting stories from each public university and will consider restorative justice for the families and their descendants.

After Chuckie Reid graduated from high school, a teacher encouraged him to go to college and study music.

Instead, he joined the Air Force and returned to his hometown after his service. He worked at Longwood’s recreation center and later found a stable career as a U.S. mail carrier.

A few community leaders urged him to run for the Town Council in 1986. He became vice mayor in 2008. “I was supposed to run one term,” he said, “and I'm still here.”

His political ward became the target of campus expansions. Many of his neighbors and constituents have moved.

Reid lost the property underneath his mother’s house. He moved the home to his own land and connected it to the existing house. His grandchildren tell him his home is a mansion: “That’s two houses in one.”

All the pain and details have been told before, he said. “It was a hurt, you know. And people still hurt,” he said. “I still hurt, but I don't show it as much.”

Ken Woodley, editor and reporter at the Farmville Herald for nearly four decades, said Longwood could have expanded into white neighborhoods. “It was one more dagger to the heart – this use of eminent domain.”

The loss of property and community was deeper in Farmville, he said, “because of Massive Resistance.”

Skip Griffin, the pastor’s son who grew up in the triangle, returned to Longwood University in 2019 to give the commencement speech. The university has taken steps to acknowledge its impact on Farmville’s Black community.

In 2019, Longwood invited Skip Griffin to deliver its commencement address. Griffin, a Harvard graduate, lives in Boston.

On a bright Virginia spring day, Griffin shared his family’s story.

“History and life have a way of moving forward,” Griffin told the students, “even if slowly.”

The podium stood near a dormitory, yards away from what was the backyard of his childhood home. Ely Street was renamed in 1981. It’s now Griffin Boulevard.

Reach Louis Hansen at louis.hansen@vcij.org.