Thousands of Flock Safety surveillance cameras captured Virginia travelers with an unblinking eye. Their data was shared and searched around the country millions of times.

By Kunle Falayi

Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO

Bridgewater, Va. - In a quiet stretch of the Shenandoah Valley, Bridgewater – a town of 6,600 – experiences crime rates well below the national average.

In fact, in the past five years, the small community has reported no homicides, one abduction, two robberies, and six motor vehicle thefts, according to FBI data.

Despite its low crime rate and small-town pace, Bridgewater is one of dozens of Virginia municipalities with a network of Flock surveillance cameras — the most widely used automatic license plate readers in the U.S. The town’s five cameras capture images of the license plates, makes and models, bumper stickers and dents of more than 60,000 vehicles every month.

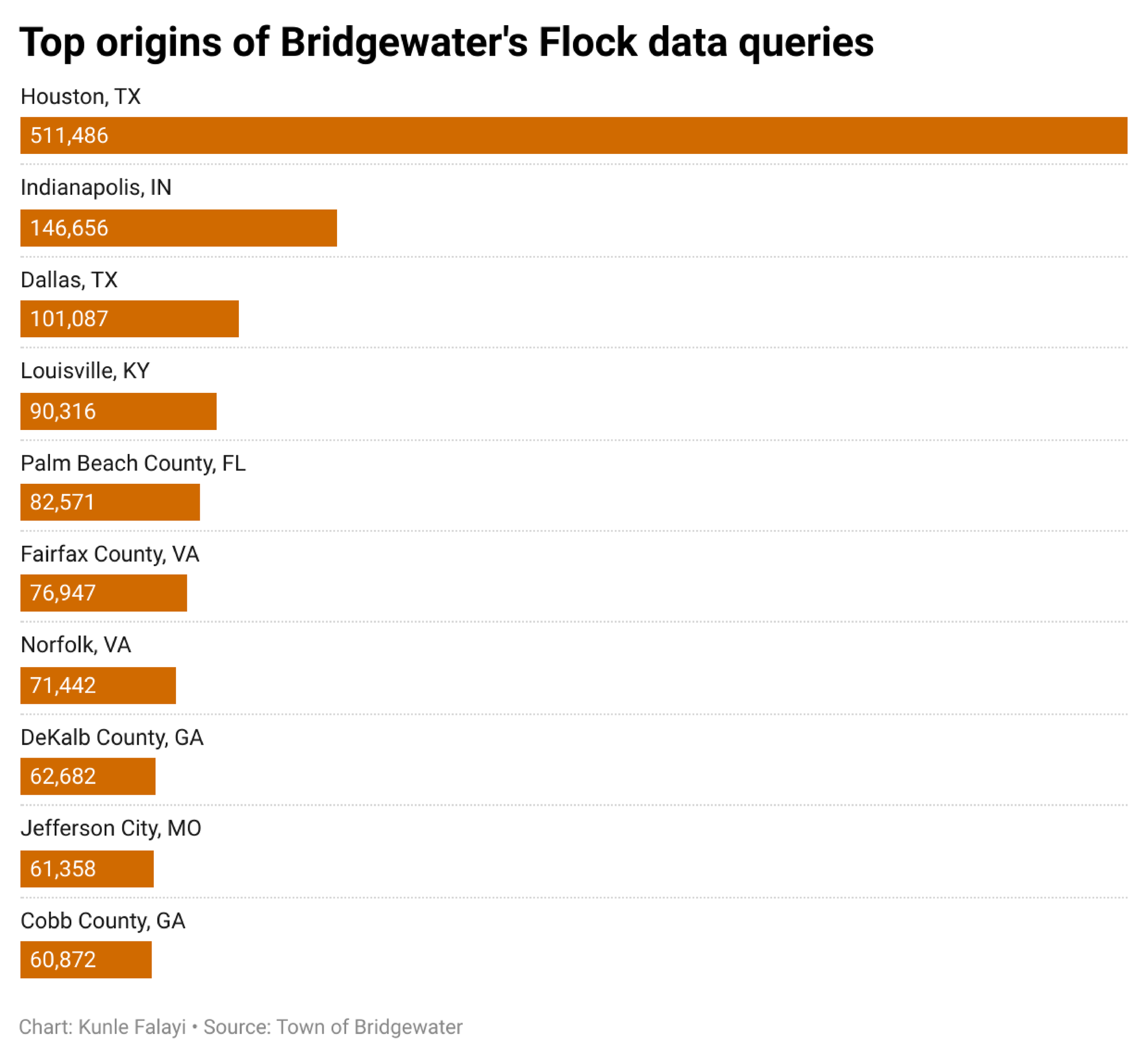

The collection of personal data and images traveled far beyond the borders of the small town: outside law enforcement agencies across the country accessed Bridgewater’s data 6.9 million times over 12 months through the Flock network, according to an analysis by the Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism at WHRO.

Network audit data obtained through multiple public records requests by VCIJ reveal the vast extent of data sharing within Flock’s nationwide camera system — a network many local residents may not have realized their personal information was part of. A new Virginia law that took effect in July has since limited the sharing of ALPR data to only specific law enforcement purposes.

Privacy experts say that the extensive access has grievous consequences for data protection and could undermine the potential benefits of the surveillance technology for law enforcement.

“It ties into a larger problem of communities opting into these databases where their information is being made available all across the country to jurisdictions they don't even know about and have no control over,” said attorney Michael Soyfer of the Institute for Justice.

The queries of Bridgewater’s ALPR data show how even small, low-crime towns have become part of a vast surveillance network that tracks the movements of millions of people far beyond local borders. It’s been used to track missing persons, stolen cars and potential violations of immigration laws, as well as sweeping up the data and routines of daily commuters and shoppers.

It also highlights the vast spread of automatic license plate readers in Virginia and the limited public oversight around their use. The growing debate over police use of high-tech surveillance and vast networks has raised alarms with privacy advocates and civil libertarians. While the spread of surveillance has comforted some communities, it has thrust others into fear.

A vast array of surveillance in Virginia, shared across the U.S.

Virginia has more than 1,000 automated license plate readers (ALPRs) scattered across the state, capturing millions of images every day, according to Deflock, a volunteer-run website that maps the location of ALPR cameras nationwide. In a small town like Bridgewater, cameras logged data from over 60,000 vehicles in just one month. In bigger cities, the numbers are even more staggering—Richmond’s 102 cameras recorded more than 600,000 vehicles during that same period.

While out-of-state agencies were not allowed to download or store Virginia’s ALPR data, the volume of search queries in Bridgewater suggests something broader. Before the state’s ALPR law took effect, anyone who drove past one of these cameras had their data made available to thousands of law enforcement agencies, and likely were included in millions of police searches over the course of a year.

In June, VCIJ at WHRO requested Flock data logs –user names and jurisdictions of those who searched the system, the times, dates and reasons for the searches – from all Virginia law enforcement agencies that use Flock cameras. VCIJ requested the public information for the period of June 2024 to June 2025.

A farm tractor drives past a Flock camera on Dry River Road in Bridgewater, Virginia, on Aug 15, 2025. Law enforcement agencies across the country searched data from Bridgewater’s cameras nearly seven million times during a 12 month period. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ

We received complete responses to our public records request from only two jurisdictions. The 12-months of data from Bridgewater and Mecklenburg County provided insight into the access out-of-state agencies had to Virginia’s ALPR system. It also shows how other Virginia agencies accessed other departments’ ALPR data.

Bridgewater is not the only Virginia locality where VCIJ found extensive outside queries of Flock data. In Mecklenburg County, Flock data was accessed more than 5.3 million times during the same period, even though the county has just 10 cameras listed on its Flock Safety transparency portal.

By contrast, cities and counties with far larger Flock networks—such as Suffolk, Norfolk, and Richmond—either declined to release their network audits or did not respond to VCIJ’s records requests filed before Virginia’s new ALPR law took effect on July 1. The law now shields network audits from public disclosure.

The case of Bridgewater is emblematic of the lack of control communities have over their data captured by automatic license plate readers, Soyfer said.

Soyfer is currently litigating a challenge against Norfolk’s use of Flock cameras in federal court on behalf of the city’s residents. The Institute of Justice argues that capturing and storing every resident’s location data without a warrant for many weeks violates the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches.

The current ALPR law in Virginia stipulates that data collected by the cameras cannot be kept beyond 21 days. But Soyfer said that duration still represents weeks in people’s lives.

“I am not as bothered about the collection of information about people who are committing crimes,” he said. “I'm really bothered about this massive surveillance of people who are just going about their daily lives, and their movements stored in the system for weeks all across the country.”

Despite public misgivings about the use of ALPRs, their reach has expanded considerably over the years. About 80% of 275 large law enforcement agencies and 35% of the smaller departments in the state said they had procured an ALPR system, according to a 2024 survey conducted by the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services. Flock Safety is used by at least 29 jurisdictions, and is just one of several ALPR contractors used by Virginia law enforcement.

“They have been an important and reliable tool to expedite investigations in time-sensitive situations, such as missing persons and abductions,” Dana Schrad, executive director of the Virginia Association of Chiefs of Police and Foundation, told VCIJ at WHRO.

ALPRs have been used in the recovery of stolen vehicles and the identification of wanted persons in the city of Fairfax, a missing person’s case in Winchester, to the identification of a homicide suspect in Henrico’s West End and a rape suspect in the town of South Hill, according to a 2024 report submitted to the General Assembly.

Increased surveillance. One resident asks: “Why would anyone want our data?”

Just after 1 p.m. on a Tuesday in February 2022, a 911 call reported a suspicious person near Memorial Hall, the oldest building on the Bridgewater College campus. A Bridgewater College police officer and a campus safety officer responded to the scene. After a brief interaction, the suspect opened fire and shot the two officers, according to Virginia State Police.

Officers John E. Painter, 55, and Safety Officer Vashon A. Jefferson, 48, died from their injuries. Alexander Wyatt Campbell, 27, was later charged and convicted, receiving two life sentences for the shooting.

This chilling incident may explain some of the willingness of this small town with a low crime rate to readily adopt an ALPR system.

One of the five cameras in the town watches the intersection of Oakwood Drive and the quiet residential neighborhood along Weeping Willow Lane. VCIJ’s analysis of network audits shows that data from the camera and the four others in the town were queried by more than 4,600 agencies from every state in the U.S. during a one-year period.

Bridgwater resident Lizzie, who declined to give her last name, stares at Flock camera outside her home along Weeping Willow Lane in Bridgewater. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ

Bridgewater resident John Fairfield is concerned about the spread of data collected by the Flock system. Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ

The idea that data captured along this quiet route could travel so far across the country surprised Lizzie, who lives on Weeping Willow Lane. From her bedroom window — less than 50 feet away — she has a direct line of sight to the Flock camera.

“That is just weird,” said Lizzie, who declined to give her last name. “Why would anyone want our data? It makes me a little uncomfortable.”

Lizzie, who has lived in the neighborhood for four years, has always seen the camera pole, but does not recall exactly when it was installed. She didn’t even know what a Flock camera was or what it did.

John Fairfield, 77, a long-time resident of Bridgewater, was less surprised about how widespread the town’s collected data had travelled.

“I am concerned with the degree to which this kind of data could be used to suppress dissent, to suppress freedom of opinion,” said Fairfield, a retired computer science professor. “I don't know how people can collect the data for use in legitimate law enforcement and not have it be available for other purposes.”

Even a limit on how long the data is retained would not give him confidence that ALPR data wouldn’t be misused. Data often travels from one server to another easily these days, he said.

A VCIJ review of town hall meeting minutes from 2022 to 2025 revealed no mention of the technology. Nor did a review of Bridgewater Current—the town’s monthly newsletter and primary vehicle for official announcements—reference the surveillance system at any point over the past four years.

“Our legal system doesn't seem quite up to snuff at the moment,” Fairfield said. “We need a much stronger set of case law and a set of traditions and institutions to prevent that sort of thing.”

After multiple unanswered calls and emails and a visit to the Bridgewater town hall, assistant town manager Alexander Wilmer said the town officials would not comment.The two town residents told VCIJ at WHRO they had no recollection of the town ever notifying the public about plans to deploy automatic license plate readers.

Bridgewater is just one of several Virginia jurisdictions that shared their Flock system data with hundreds of agencies across the country, many of which are in states that do not have laws regulating the use of automatic license plate readers or the data they capture. Only 16 states, apart from Virginia, currently have such laws, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Privacy advocates say this extensive access in any location is a potential danger to civil liberties.

In a July statement, the American Civil Liberties Union said Flock Safety is now using the data collected through its cameras to analyze the driving patterns of motorists to determine if they are suspicious.

In response to VCIJ’s inquiry about this, a Flock Safety spokeswoman denied using ALPR data for this purpose, also known as “predictive policing.”

“We do have AI tools that can help law enforcement surface leads faster and more easily, but there's no predictions involved in this,” the spokeswoman said.

A privacy advocate, Clayton Tye, said communities would be worried if they knew that the Flock cameras have the potential to map their workplace, shopping habits, kids' school, place of worship, and other information within days.

“That data being fed into a national database should make anyone uneasy in such a fraught political climate,” he said. “Whether it is a small town cop or a task force officer, no one should have that level of access to the movements of the nation without a judicial warrant.”

Reach Kunle Falayi at kunle.falayi@vcij.org